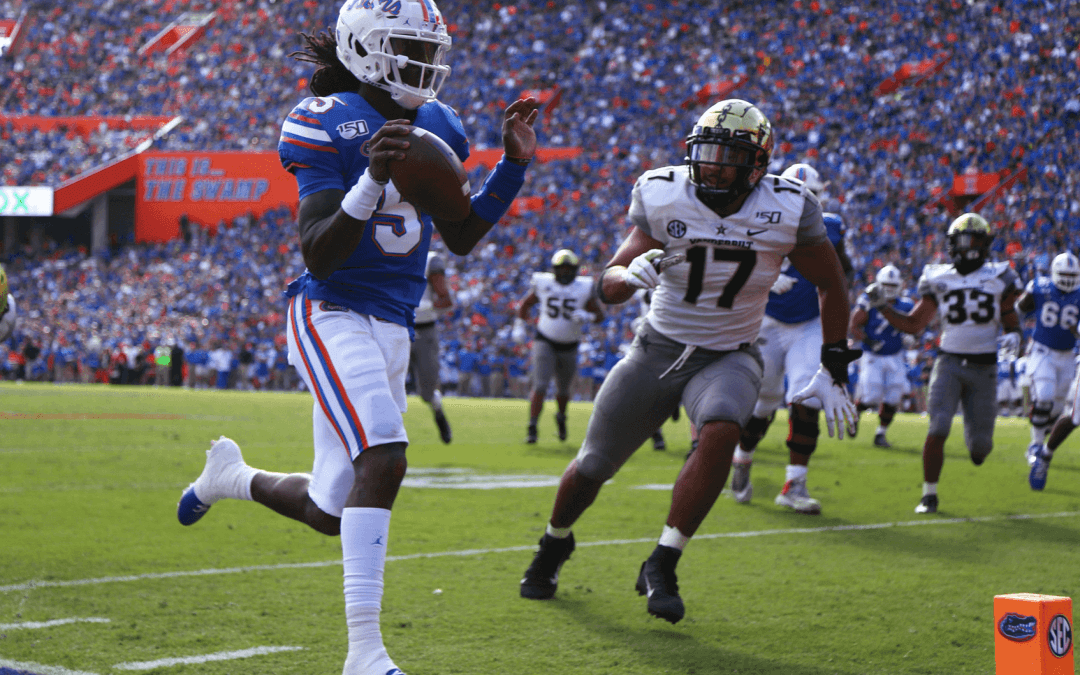

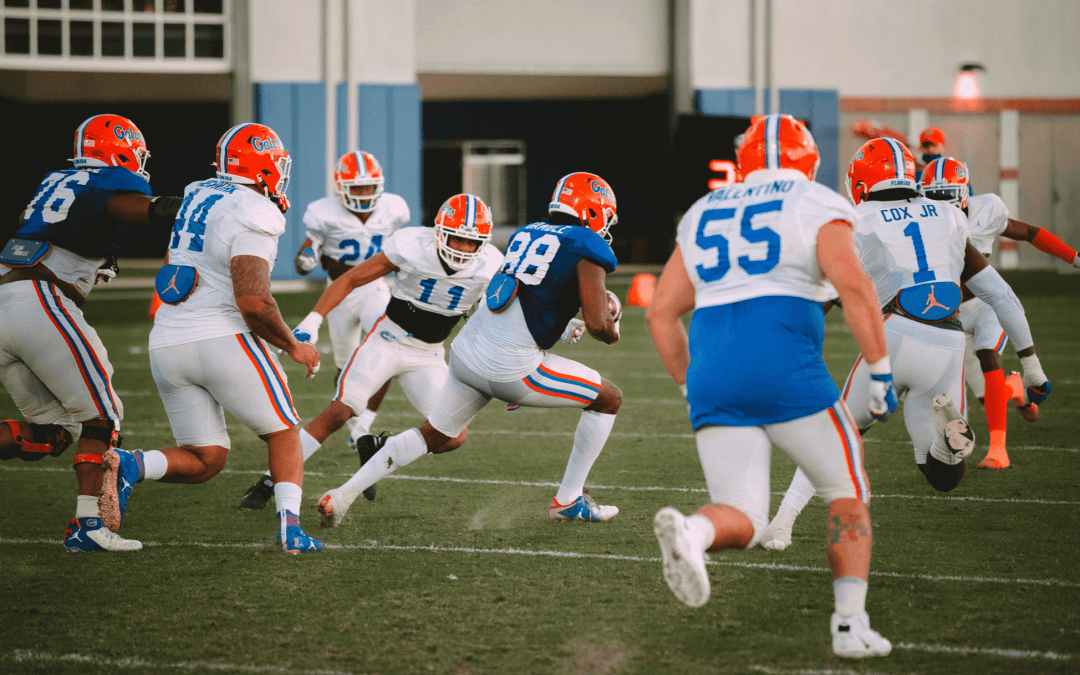

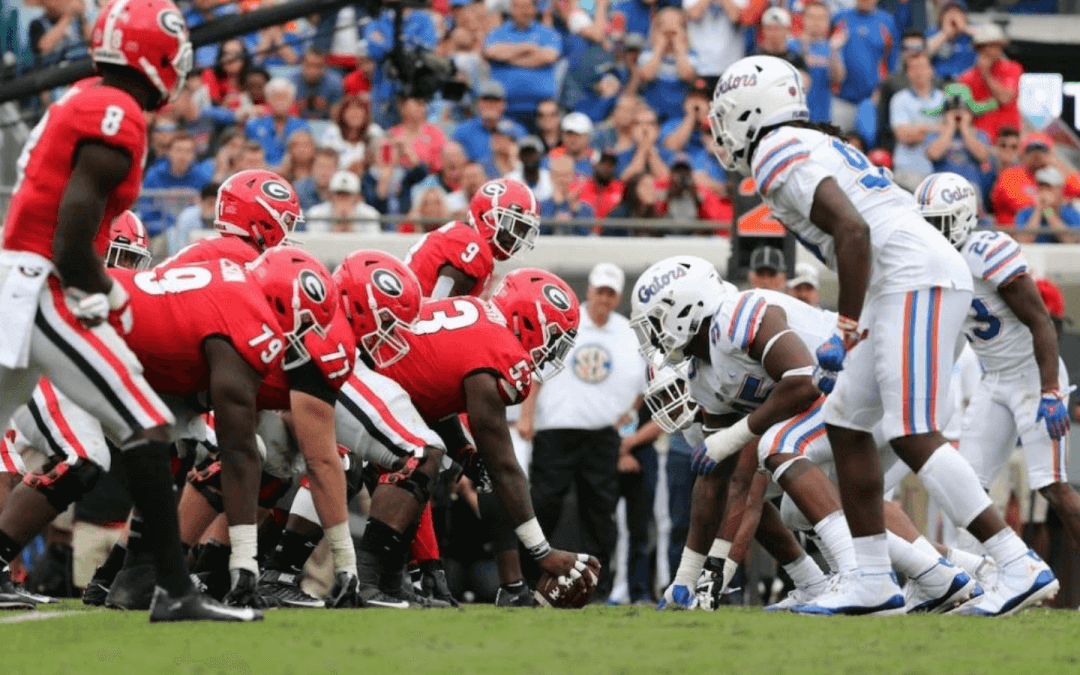

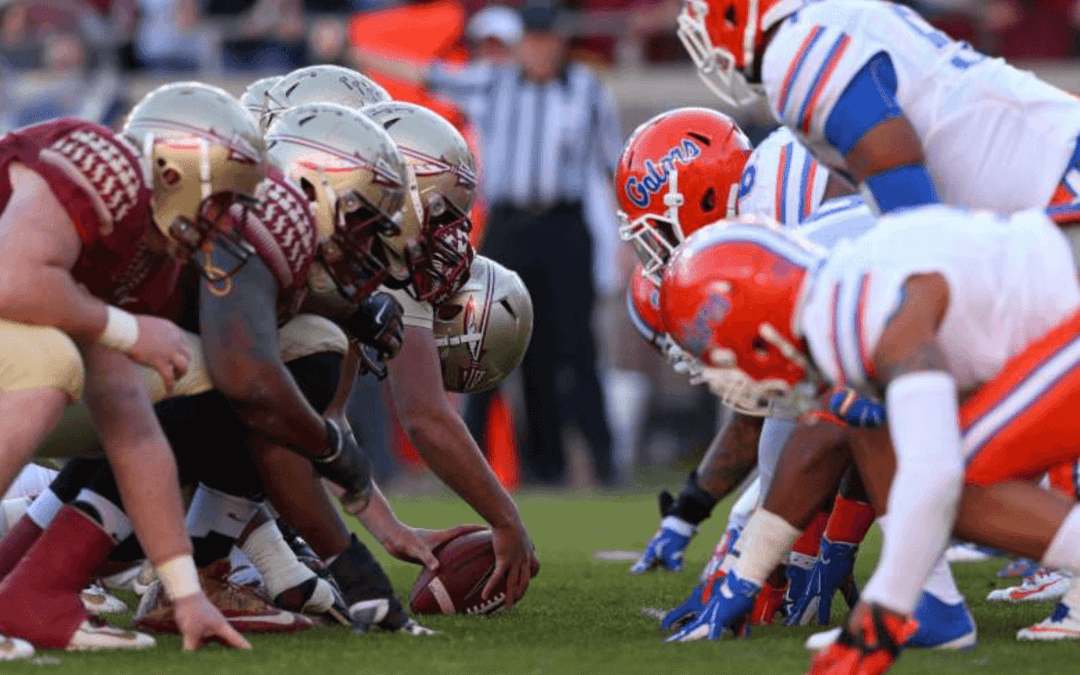

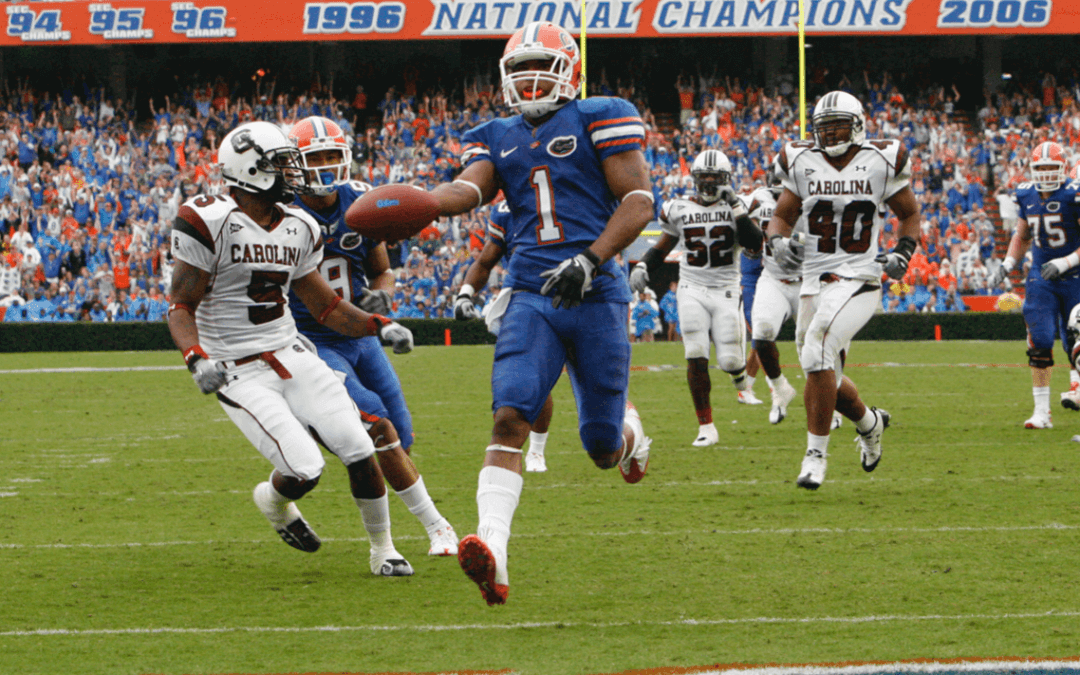

Florida and Georgia for the 93rd time in Jacksonville Saturday afternoon and on paper, the game is already one of the storied rivalry’s biggest. You know the stakes.

A win for Florida all but officially seals the SEC East for the Gators, leaving only Vanderbilt with a chance, and that chance all but officially a pure mathematical opportunity. A win also situates the Gators in the center of the playoff conversation as the committee meets for the first time Sunday.

A win for Georgia and the two-loss Bulldogs control their own destiny instead, despite the rout at home against Alabama and the three touchdown lead squandered in Knoxville. A Bulldog win would do wonders with a torn Georgia fan base, one that wonders whether 15th year head coach Mark Richt, as good a man as you’ll meet, is still the right man for the job, now 10 years removed from the school’s last SEC Championship.

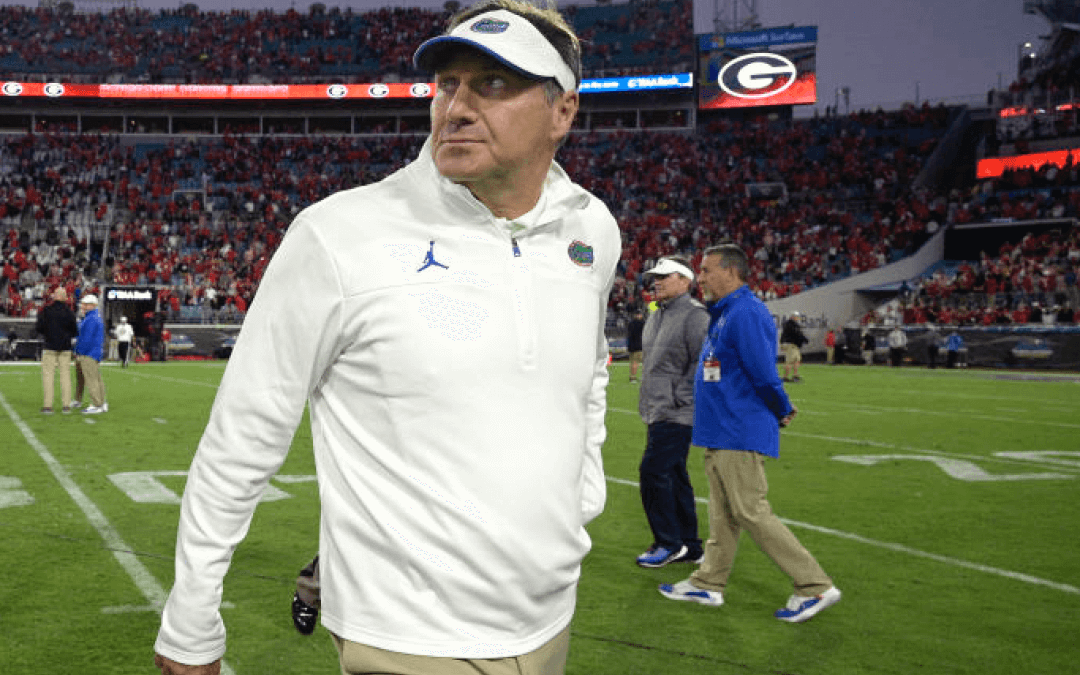

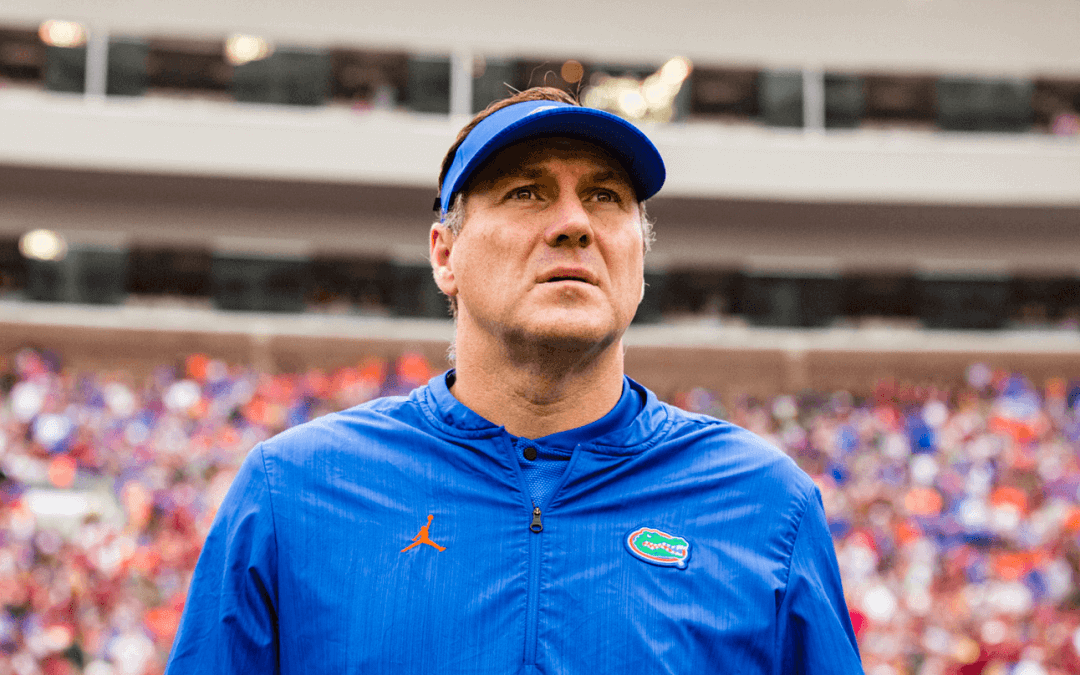

Heady stuff, and that’s before you get into the complex and indeterminate nature of rivalry history and psychology, and what a win would mean for a first year coach whose program turnaround is ahead of schedule, or how Mark Richt coaches this game “tight”, or how Florida coaches in particular are defined by their ability or inability to defeat this particular rival.

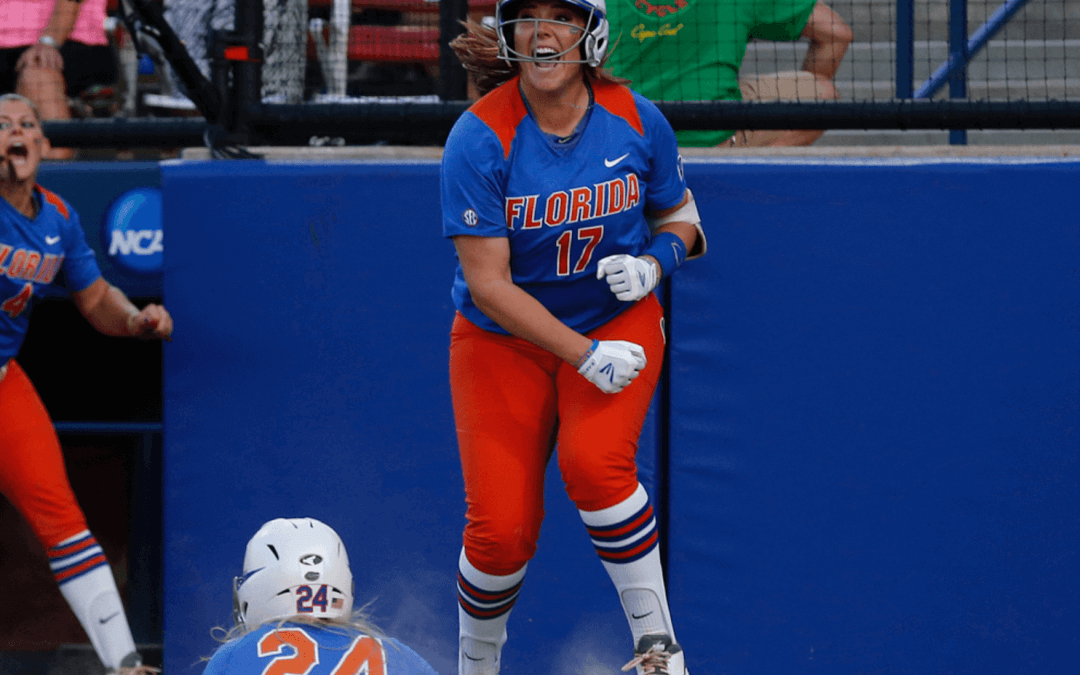

For Georgia, Florida is enemy number one, with a nod of disaffection to the nerds from North Avenue. What for nearly 70 years was largely an exercise in Georgia dominance has become, over the last quarter century, a frequent scene of horror and heartbreak, with only the last few years providing respite. They arrive in Jacksonville early and when they win, they bark and yell and party well past late.

For Florida, the game is often slotted by fans as second, behind the end of the November clash with Florida State. That’s an assessment that makes older alumni (and often their children, second and third generation Gators) bristle, but it’s an understandable disagreement. When your school usually wins, your heart hasn’t been bruised and you have less battle scars to wear. Florida State is in-state and Gator alumni that stay in-state work with more Seminoles, have more water cooler banter. And most remember the 90’s, when Florida and FSU was influential in the national title picture almost every season. So it’s true that there are reasons to privilege one game or the other.

For me, the biggest rivalry game Florida plays will always be Georgia. The shallow leading edge of the Florida-Florida State rivalry is marked by Florida State fans’ insecure hatred and Florida fans’ smarmy dismissal. The Florida-Georgia rivalry is led by something richer, a lengthier history, conference ties and championship implications and a neutral site atmosphere unique to southern football. I suppose one could make the argument that UF-FSU matters more because of recruiting, but most analysts are cynical that recruits pick a school based on the outcome of games and the truth of the matter is that Florida, FSU and Georgia are recruiting the same players anyway. Social media, the burgeoning cottage industry that is football recruiting and the growth of college football nationally has diminished the significance of one of the old sacred cows of college football, especially in the talent-rich states of Florida and Georgia. Shut down your state’s border and you’ll always win is now “Keep as many at home as you can, and you’ll compete for championships.”

The best rivalry games are this way, heavy with drama and meaning, ripe with history and biography waiting to be written. Florida and Georgia always has intrigue and meaning and often has drama. This Saturday, it has all of those things. It’s the game you spend an offseason dreaming about, happening in a season that for Gator fans has felt like a dream.

***

When I was a student, and for a few seasons after that, I’d head to Jacksonville Thursday night or Friday morning, and find myself feeling lost on the familiar roads that lead the way to the childhood home of my mother. I just couldn’t wait to get to the Cocktail Party. The drive through Waldo, a city so poor it needed a corrupt police department to pay city bills is first, and there’s still the giant “G” flag hovering over a peanut and BBQ stand just before you peel off Waldo Road onto 301 North, a reminder that this game has a grip over this part of the state. After that, you drive past US Department of Forestry outposts and nothingness until you reach Starke, a city that’s only more than a railroad outpost because of its proximity to the local prison, with a downtown straight out of Back to the Future in 1955. There’s the Florida Twin theater, named for its two screens, a clock tower and a war monument across from a small town deli where you can get a cup of coffee with chicory and as good a salami sandwich on rye as they have south of the Mason-Dixon.

The deli is located near what used to be an old insurance shop, which was run by Charley Johns before he became a state legislator and later, after the death of Dan McCarty, Florida’s governor. Johns was leader of the Pork Chop Gang, a group of Florida legislators that supported McCarthyism and fought tooth and nail to maintain segregation. It’s a dark reminder of a different, sad time in a beautiful town that often feels like it is dying. Johns, who went to UF for a few months, couldn’t hack it and dropped out, only became governor because Dan McCarty died in office, and at that time, as President of the Florida Senate, Johns was next in line. When he ran for stand-alone election, in 1955, he was defeated by LeRoy Collins, who was the first southern governor to argue for integration on moral necessity grounds. My grandfather was McCarty’s Chief-of-Staff, wouldn’t work for a segregationist and quit when Johns took office, only to help Collins get elected two years later, shortly after the birth of my father. The only year Johns was in office, Georgia beat Florida. With integrationist governors, Florida won 10 of 12 vs UGA, their best spell in the rivalry until 1990 and the arrival of Steve Spurrier.

I suppose you could say my family’s politics have always leaned towards compassion, justice and beating Georgia.

***

Calum Grant was born in Orange Park and grew up in Middleburg, Florida just off US 17 before he went to school in Athens. That’s my biography (grew up in Atlanta, went to Florida) in reverse. Like me, he used to head to Jacksonville Thursday evening or Friday morning on game week. He liked to see his mom and bring his laundry and go look for redfish in Black Creek and Doctor’s Inlet, where they congregate this time of year because of the warmer water. Like me, he’s a father of two girls now, and it isn’t as easy to steal away. We met and became friends at Florida-Georgia in 2002. He called me Wednesday to tell me he wouldn’t be down until Friday night.

“No fishing for me this year. Weather was going to be great for it too,” Calum says, quickly transitioning to football, “always fun to make it down when the stakes are bigger though.”

Two weeks ago, after Georgia beat Missouri, Calum texted me “Dawgs doomed in JAX, can’t pass ball, no Chubb. Ugh.” As the game approaches, he’s singing a different song.

“Mark Richt teams are great at winning back against the wall games,” he tells me, “plus I’m hearing Faton Bauta may play too, give us a zone read look that will make Sony Michel (UGA’s über-talented replacement for Nick Chubb) much more difficult to stop.”

He isn’t wrong about any of it. Richt’s teams have struggled in games with great expectation since his arrival in Athens in 2001. This year’s Alabama game or the infamous blackout Alabama game in 2008 come immediately to mind.

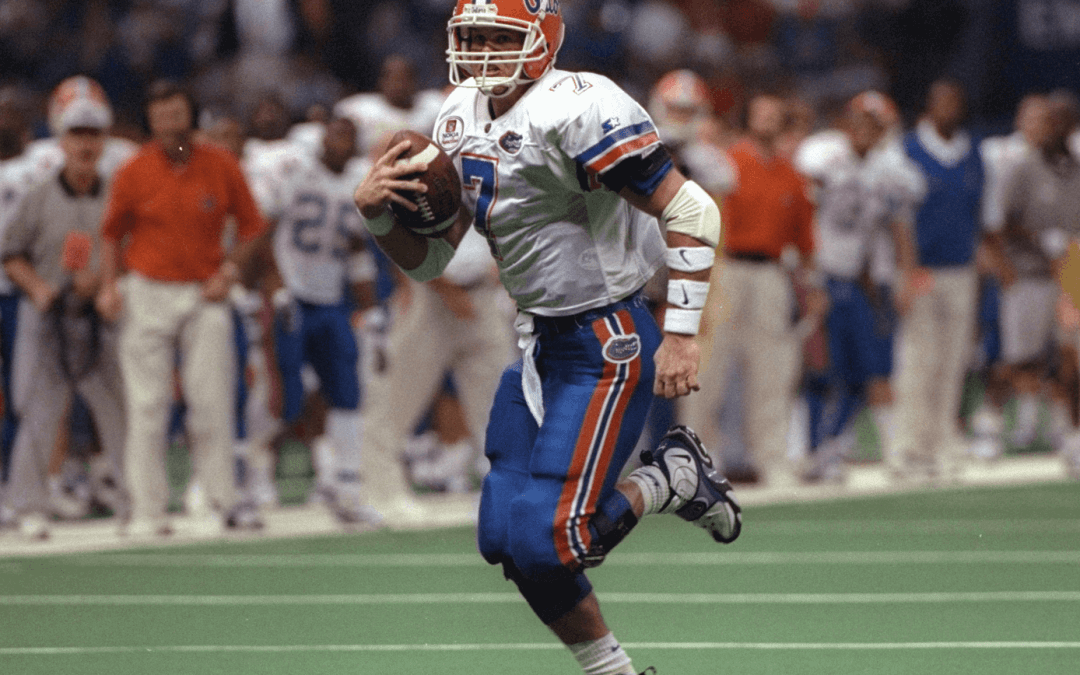

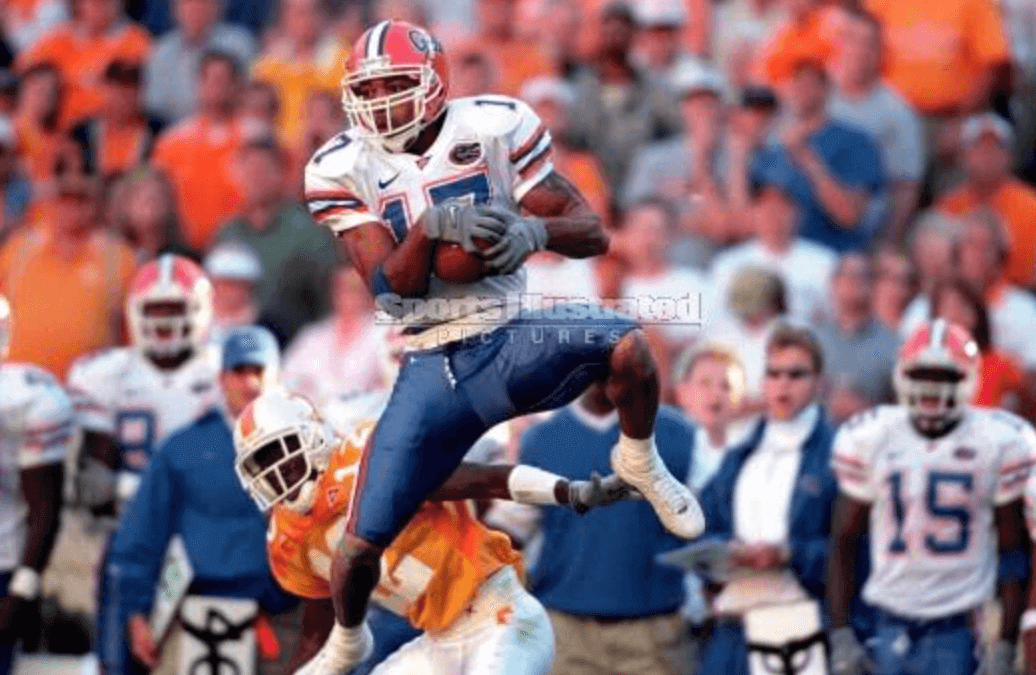

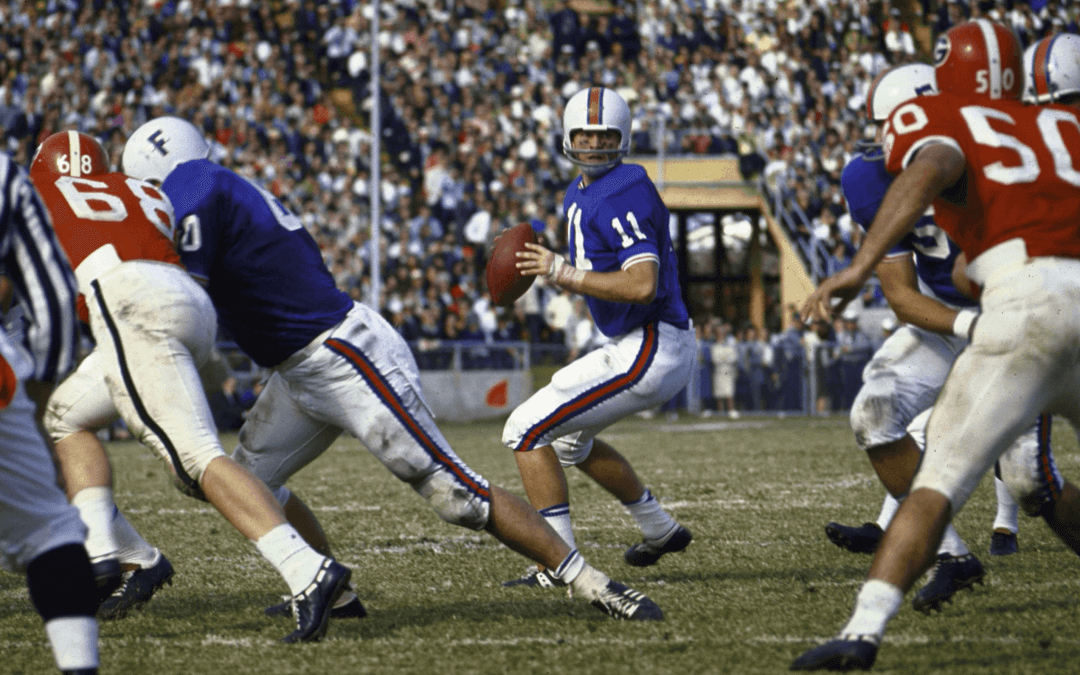

Or take the 2002 game, where Calum and I met at a tailgate. The only night game in Jacksonville in recent memory, a 4-3 Florida clipped an undefeated Georgia 20-13 behind a Guss Scott pick six of DJ Shockley and behind a tremendous performance from quarterback Rex Grossman, who led a game-winning drive in the 4th quarter and completed 37 passes while playing with and through the pain of a sprained knee. It was the only game UGA would lose all year, and prevented UGA from playing for their first national championship since the Jimmy Carter administration. There are other examples of UGA underperforming in Jacksonville- including last year’s Florida romp where the Gators ran for 418 yards and cost UGA a trip to Atlanta.

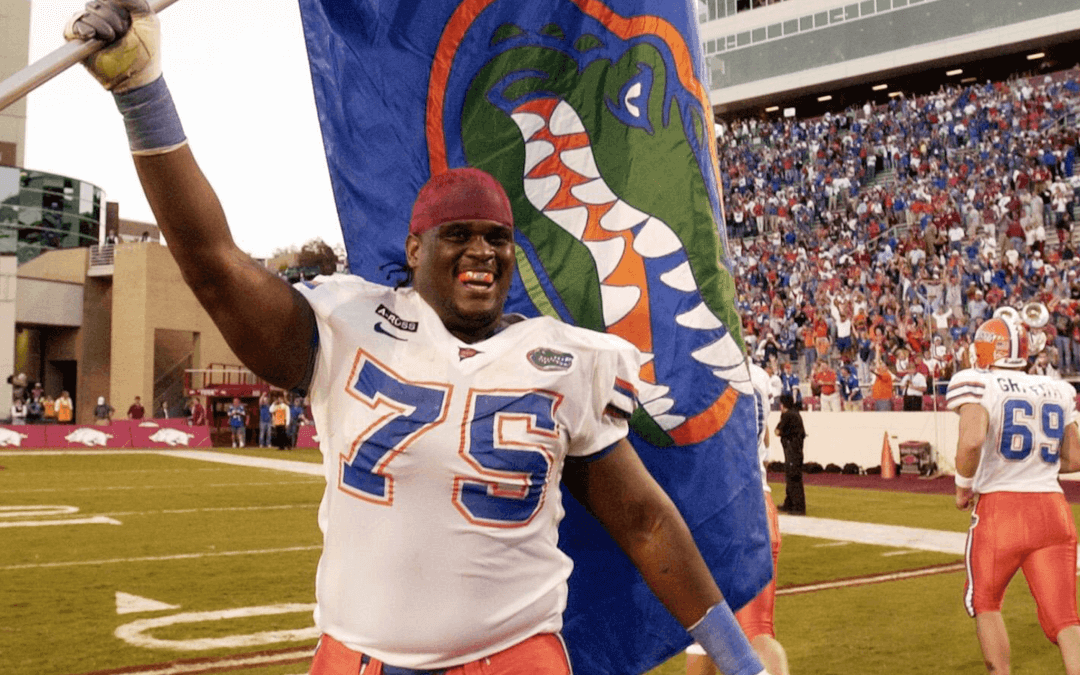

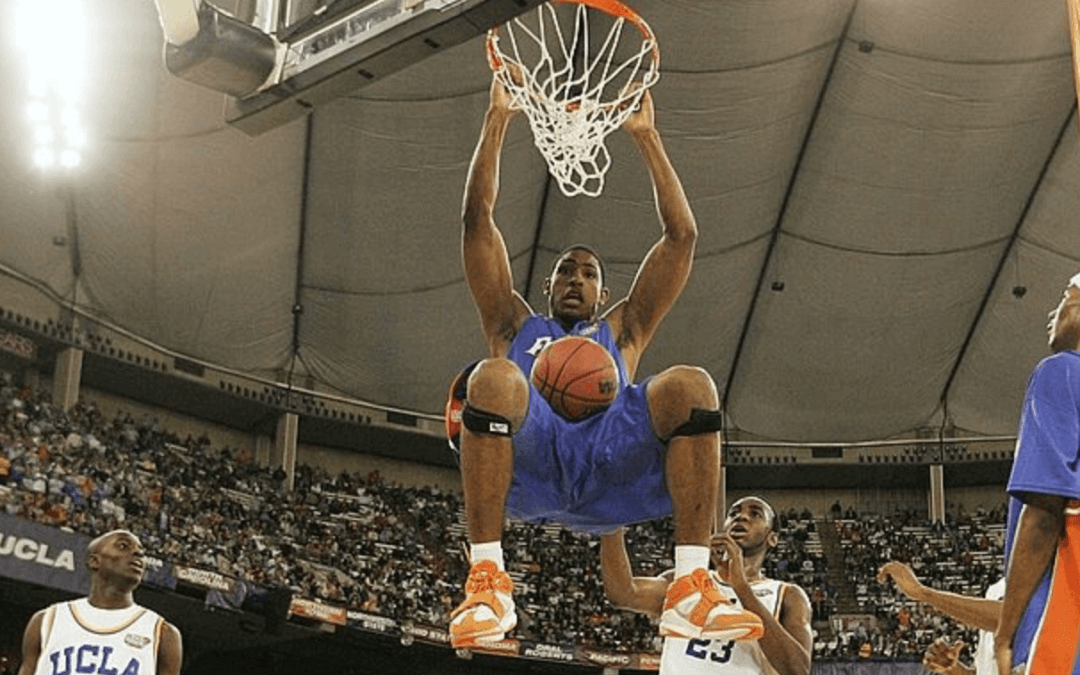

Yet Richt’s teams tend to circle the wagons. The 2012 Bulldogs had Aaron Murray and Todd Gurley but they also lost 35-7 to South Carolina and narrowly escaped Kentucky after that heading to Jacksonville. Following a get-well bye, they simplified their offense and stuffed the Florida running game, beating the undefeated Gators 17-9 and denying the Gators a trip to Atlanta. UGA’s bid for a national championship berth fell five yards short against Alabama in Atlanta, but the written-off Bulldogs had enough to stain Florida’s best season under Muschamp. The Bulldogs rallied in similar fashion in 2011, using a 24-20 win over Florida to put a two loss start to the season behind them and advance to Atlanta. For all the heartbreak Mark Richt has suffered in Jacksonville over the years, there have been some Saturdays bathed in red and black glory too.

“We have a tremendous defense,” Calum told me hopefully last night, baby crying in the background. “We just have to make enough plays with Michel and (senior wide receiver and Gator killer) Mitchell to win the game.” He isn’t wrong.

“And I know we’ve got the better kicker,” he adds, before I hear his wife screaming about diapers. He isn’t wrong about that either.

***

In college, when I wanted to think, I’d grab some music and a cup of coffee from Maude’s and drive out of town, past the Gainesville airport and towards Waldo and the run-down towns that litter the drive to Jacksonville. I did this enough that when my friends couldn’t find me, they’d assume I went on a drive, and even bought me a road atlas when I graduated.

Earlier this month, the day Will Grier was suspended, I drove that way again after a particularly difficult visit with a client of mine who is in the county jail. I was thinking of the client and had just heard about the quarterback and just drove for half an hour or so. It was a postcard October day, seventies and sunny when the rest of the country was getting its first snap of autumn cold, and I felt warm and at home, despite worry. I know I’ll do all I can for my client. I know that if Florida lose to LSU, they’ll still be able to accomplish Atlanta and maybe more if they beat Georgia.

As chance would have it, I’ve lived most of my life in either Gainesville or Georgia, only a few hours from Jacksonville by interstate or highway. Whether you head down to Jacksonville from Atlanta or drive from Gainesville, most the places you pass or drive by along the way are geographical afterthoughts, and about as “southern” as any place you’re likely to find in modern-day America.

You have to understand, “southern” no longer means cotton fields, plantations and beautiful belles waiting to escort you to Big Daddy’s formal ball, though on a game day anywhere in the southeastern United States, there’s some of that, whether it’s UGA girls in those black and red cocktail dresses or Bama girls in houndstooth hats or UF girls in orange and blue sundresses. Still, despite all the changes history has brought us, there’s still places like Starke and drives that conjure up the idea of a time portal. And certain things remain true about the south. First, the south is beautiful, small towns and forests and miles of lush, green fields. Second, it’s where all the good music you’ve ever heard was born. Soul, rock, country, blues, all of them from south of the Mason-Dixon line. Third, college football. In the south, good football and music are like sunshine– you just can’t escape it.

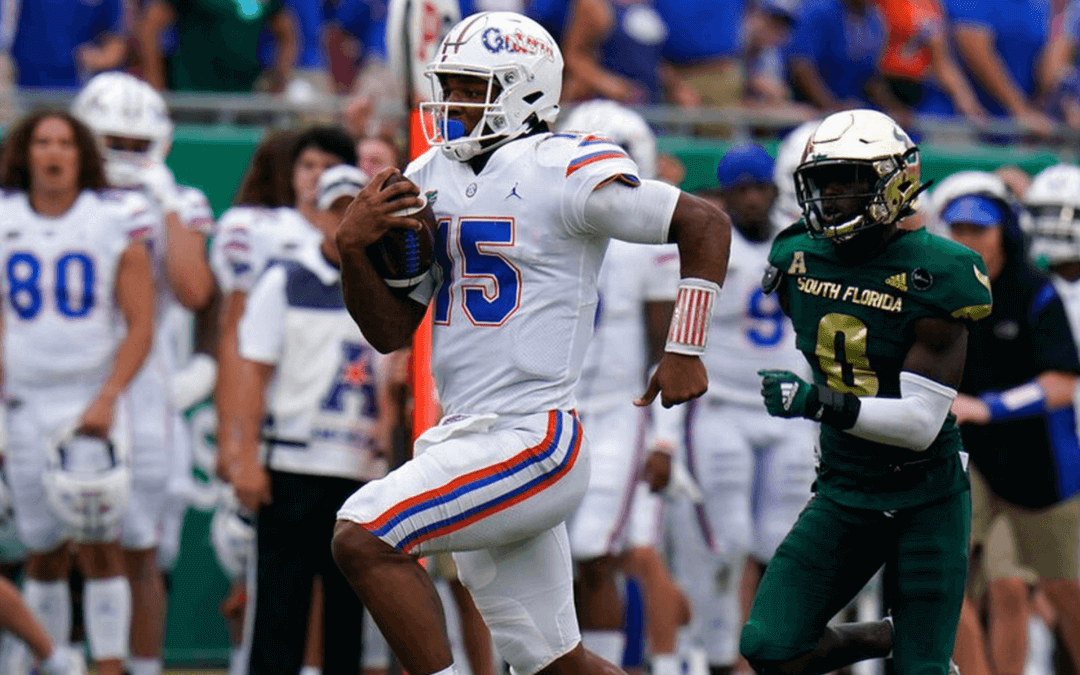

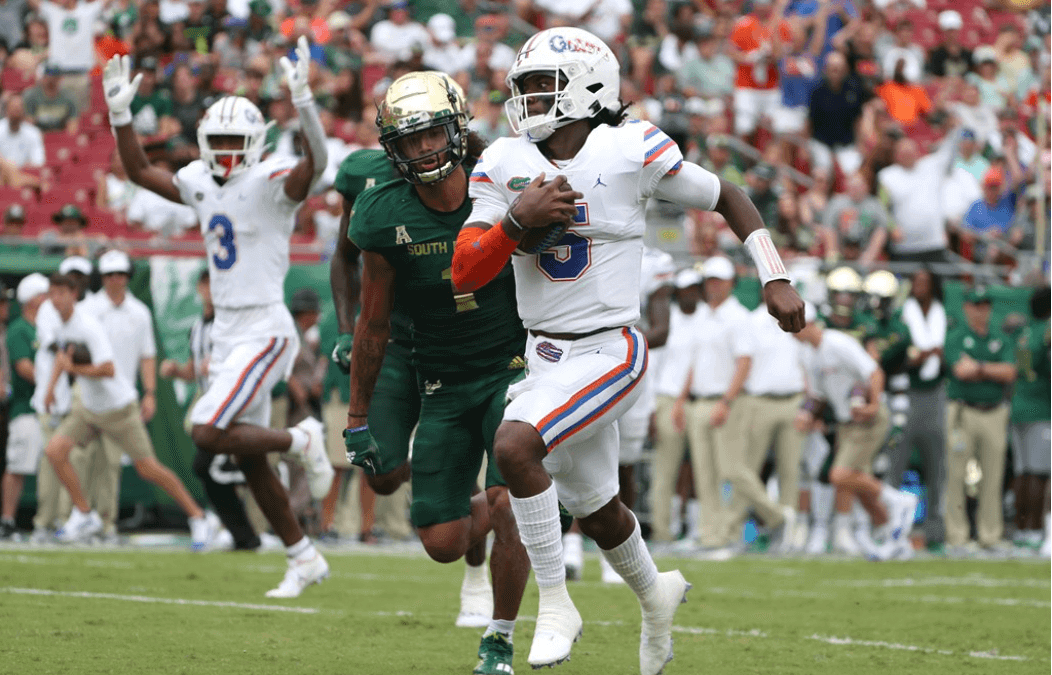

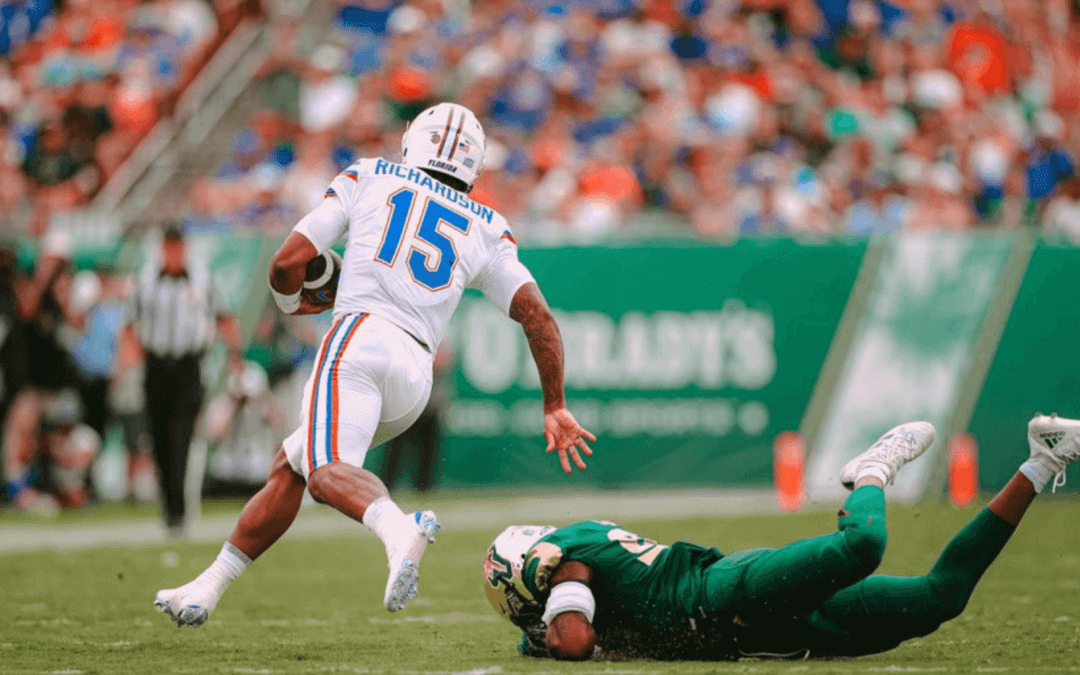

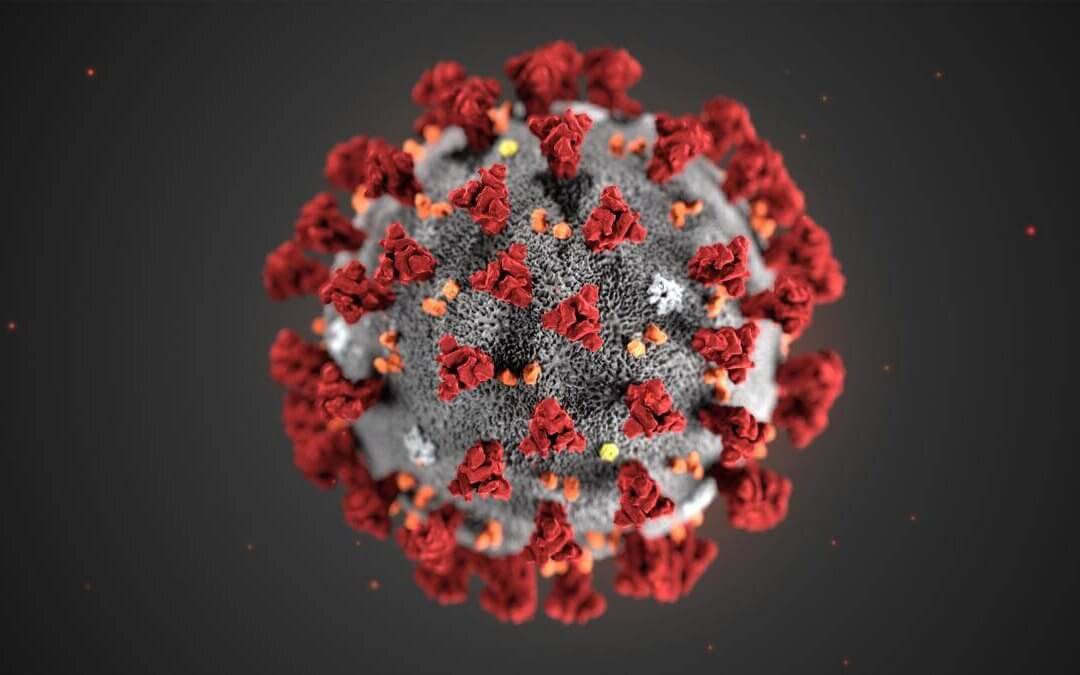

The south can’t escape the old history either though, the kind I remember driving through Starke, and it is hard to parse through the discussion about Will Grier’s suspension and the concern about the length and fixation on his appeal without immediately thinking of the young man who has replaced him, Treon Harris.

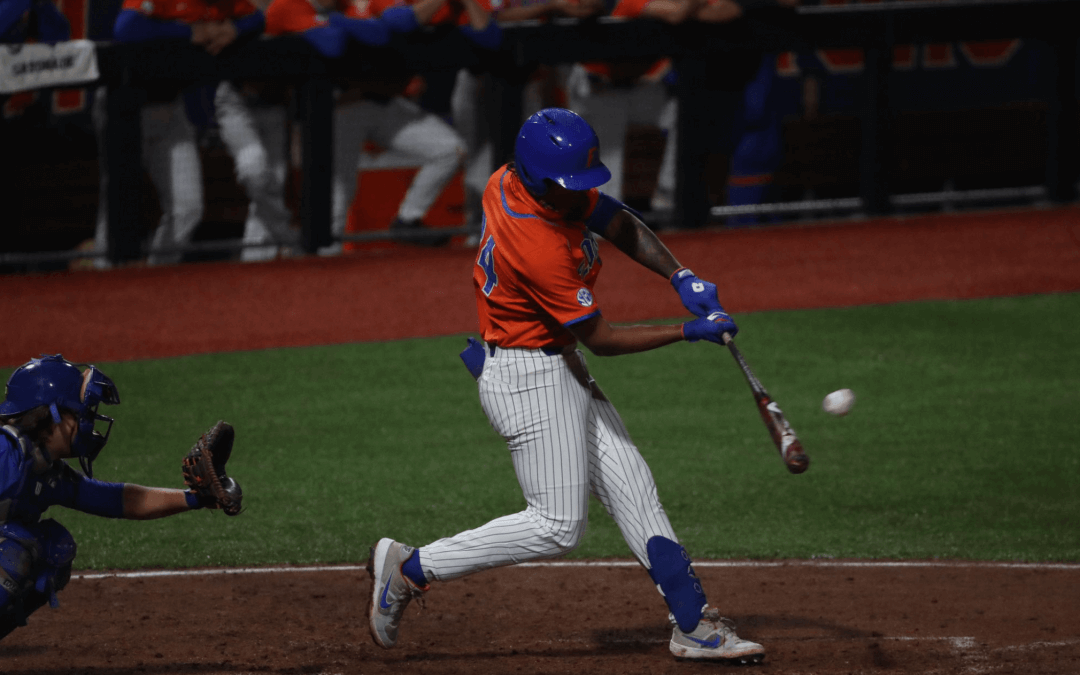

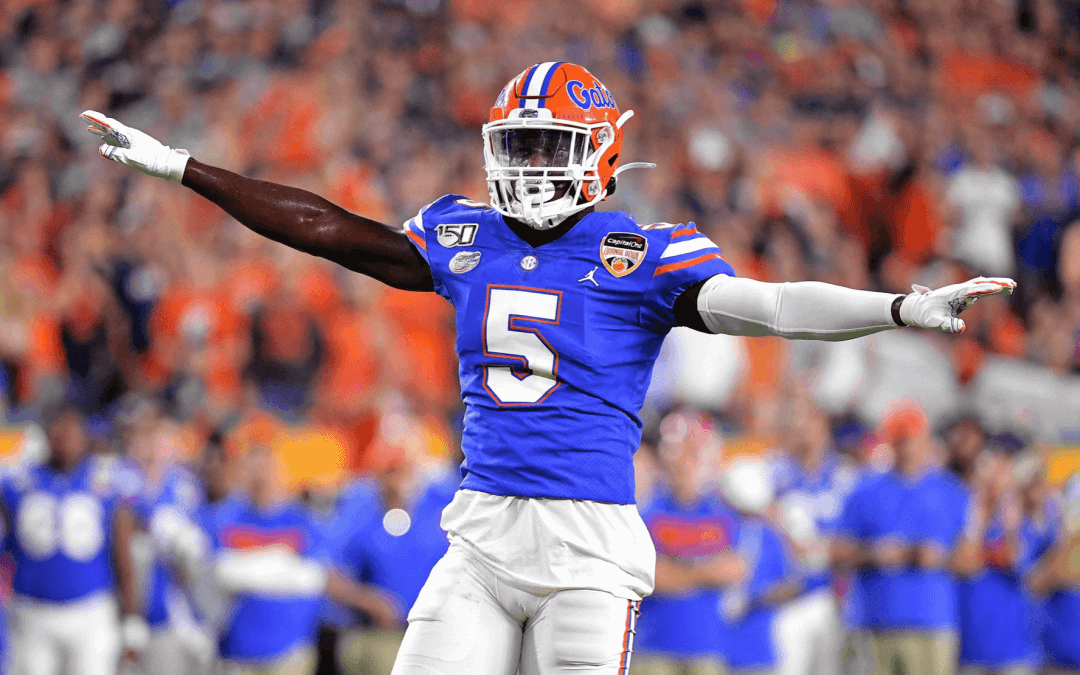

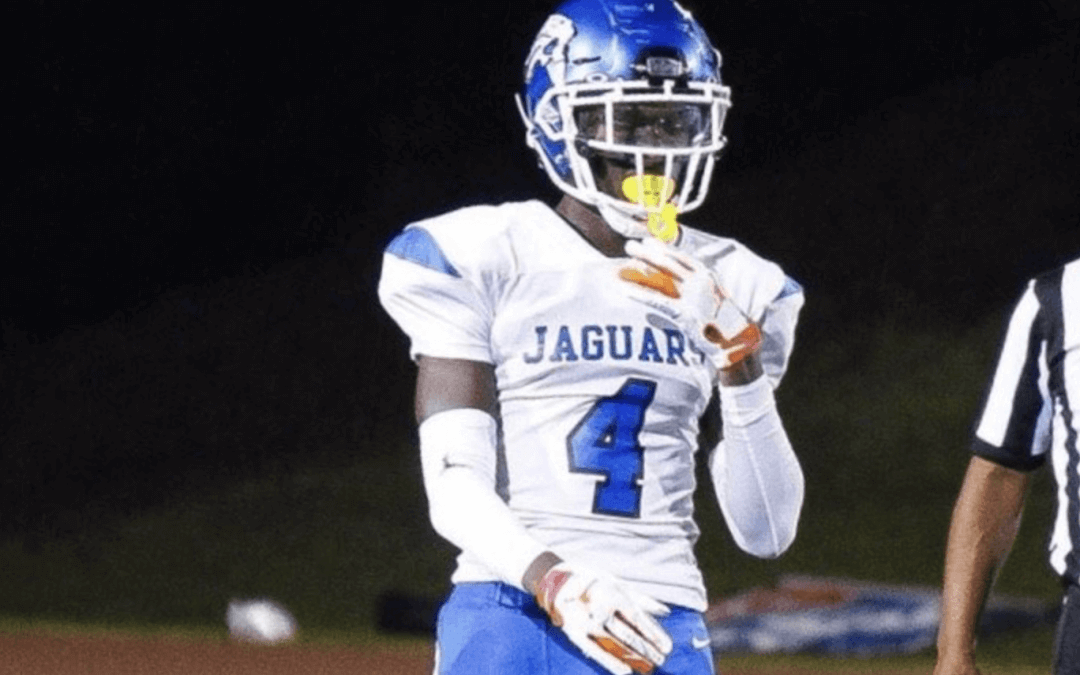

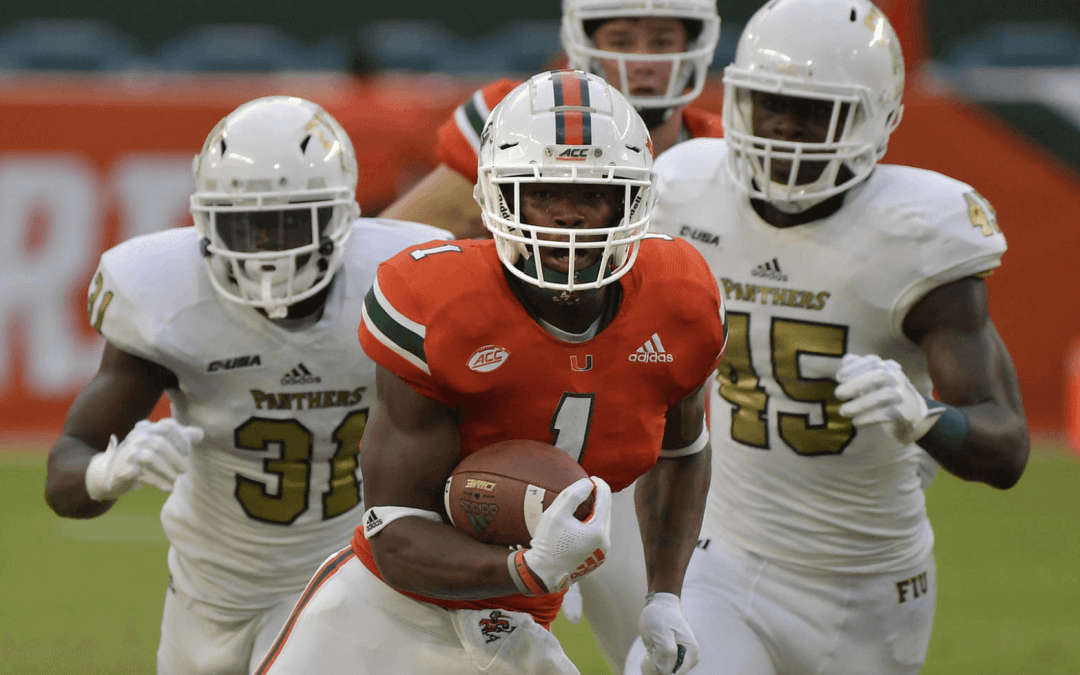

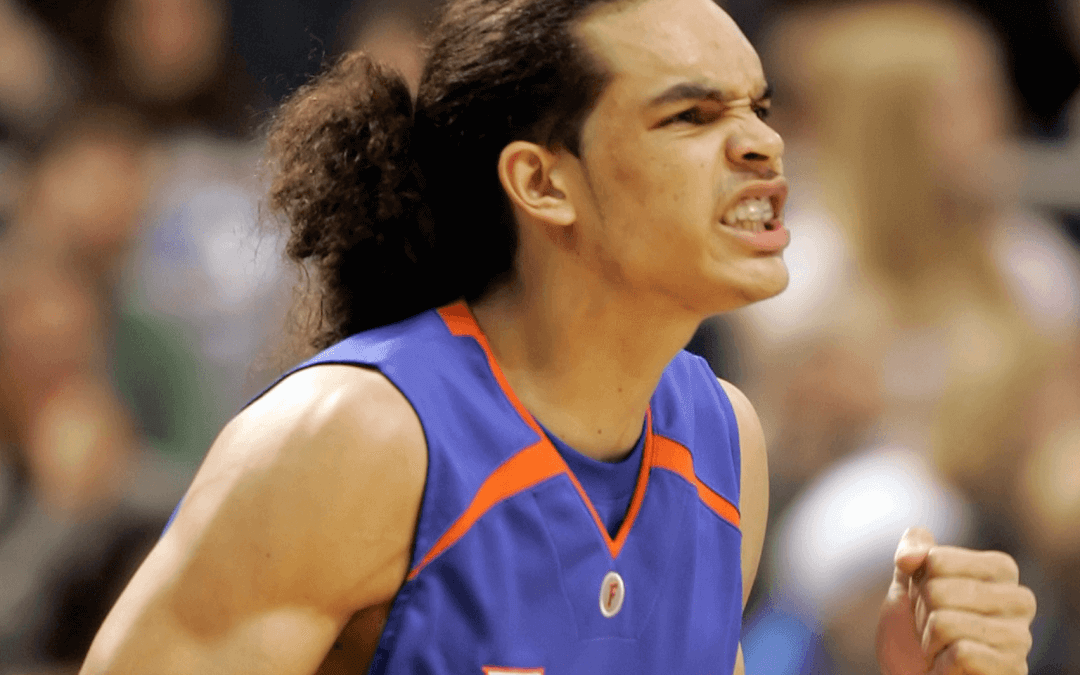

In many respects, Harris’s mere presence at Florida is proof of the power of sport as social agent for change in the south. Harris is, after all, only the sixth black player to start at quarterback for Florida, and three of those have come in the last five seasons. There’s a history of ugliness and violence and shame from Starke to South Dade County and all manner of points beyond and between, and not all of it is gone because the law was changed. But college football, maybe more than other sports, has helped. Some of the reaction to Harris taking over has brought back some ugliness, and the fixation on Grier’’s appeal, featuring ill-timed tweets and consistent updates, has been less than settling when the reality is Florida will succeed or fail the remainder of the season with Harris behind center.

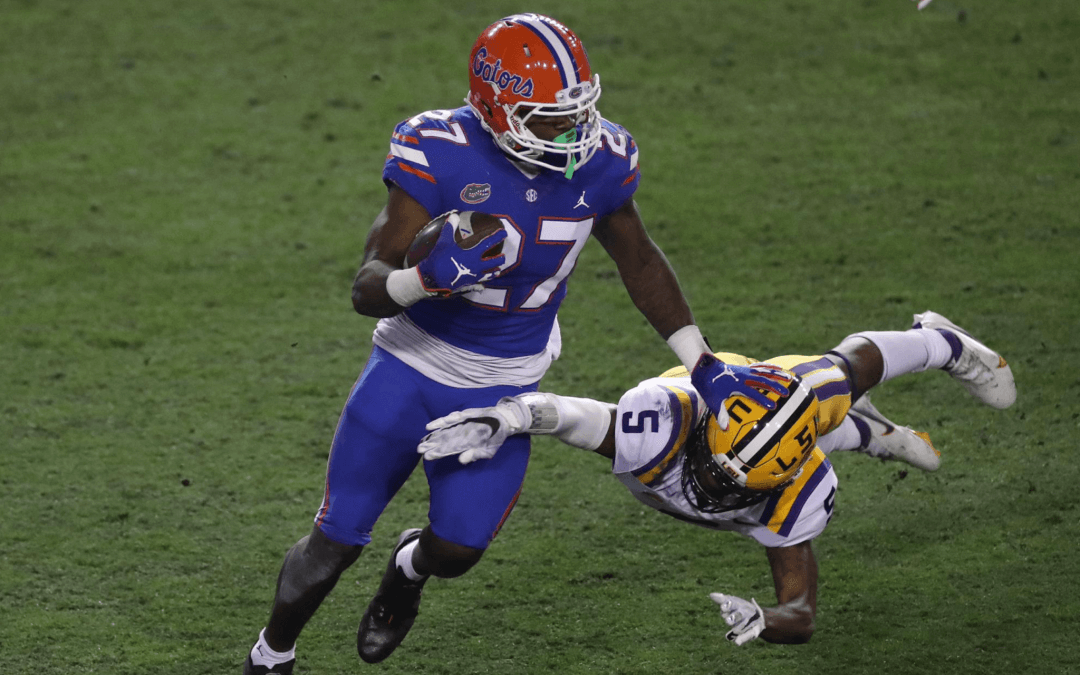

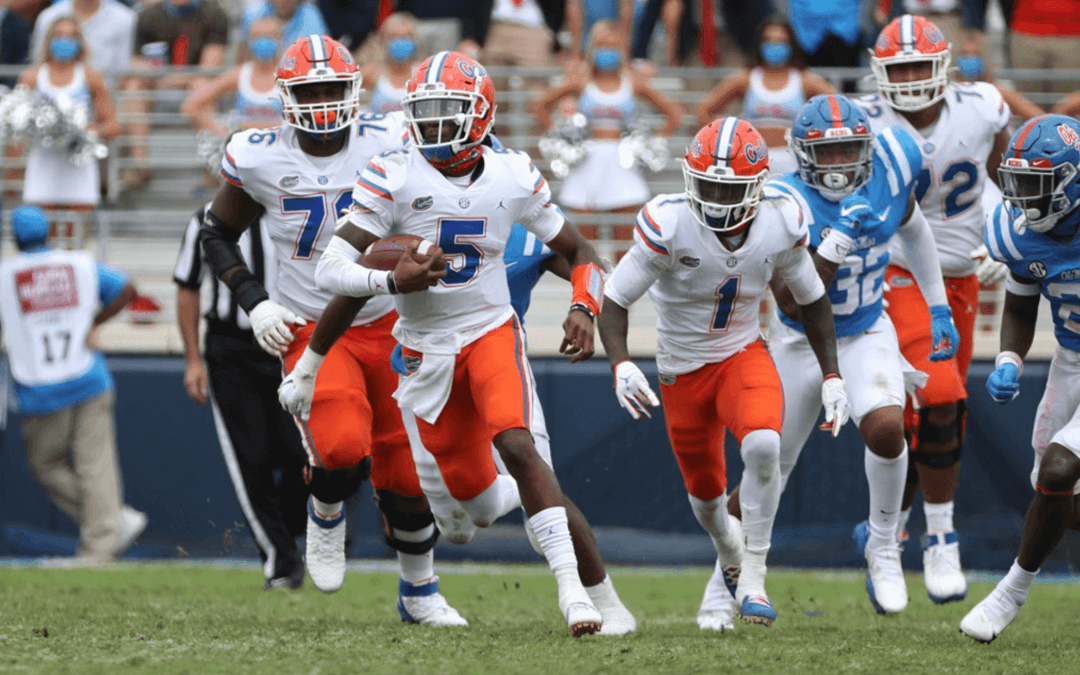

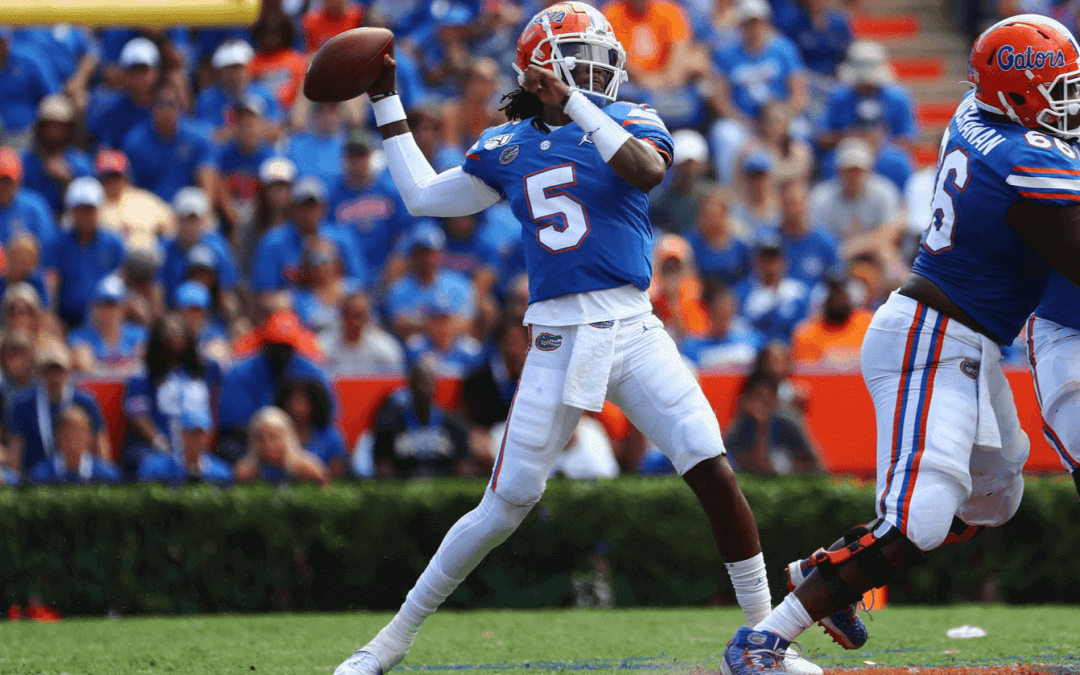

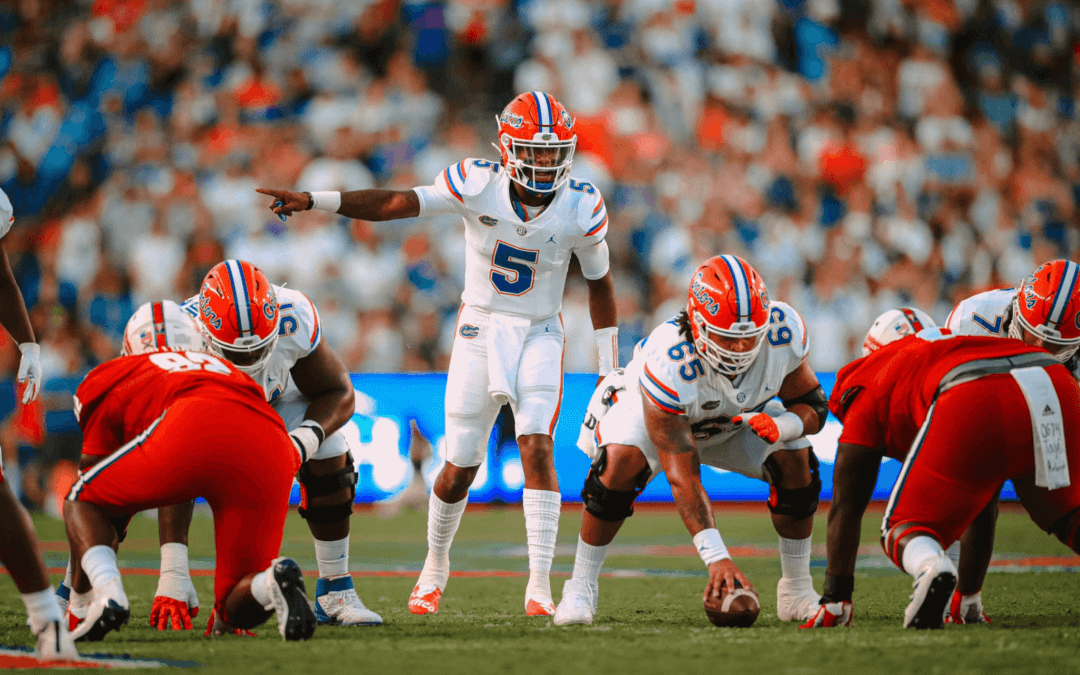

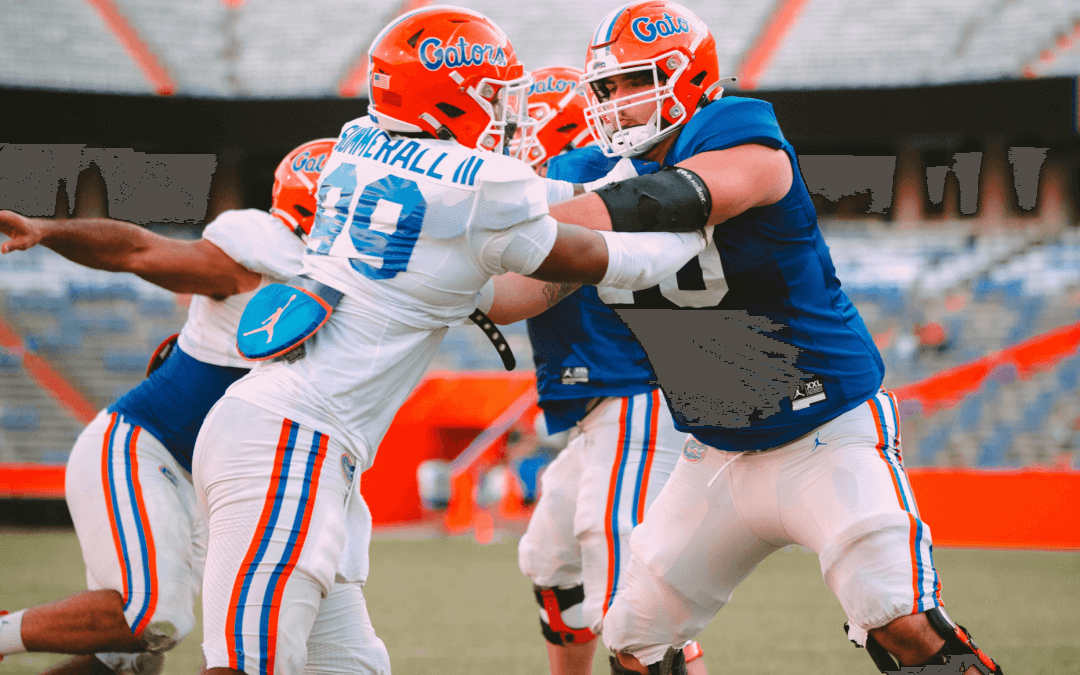

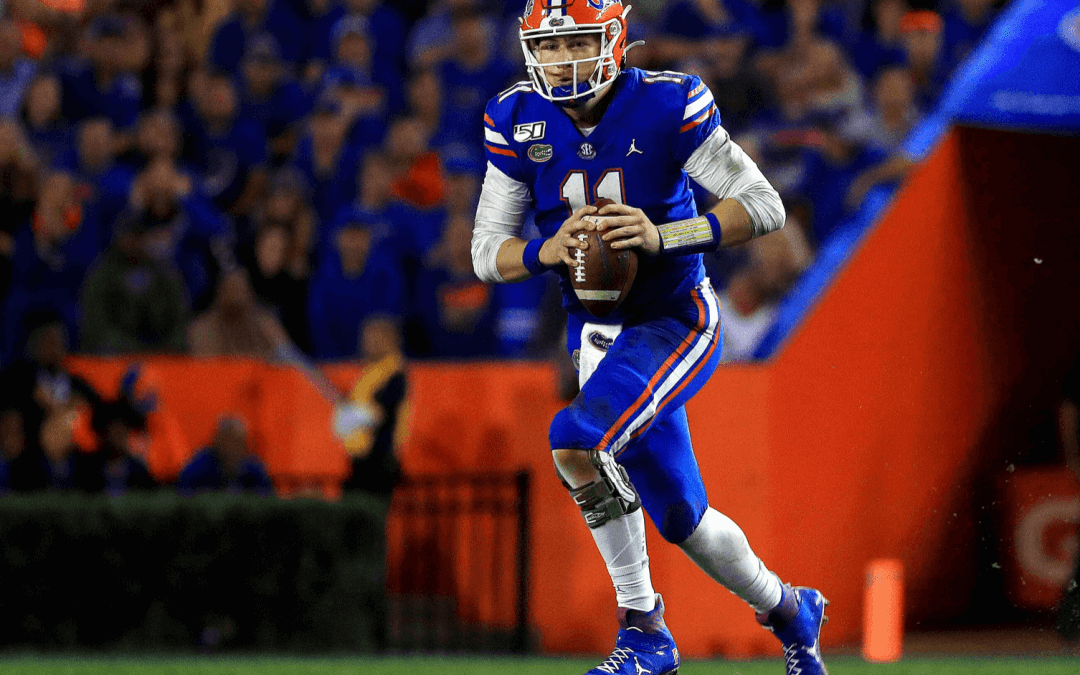

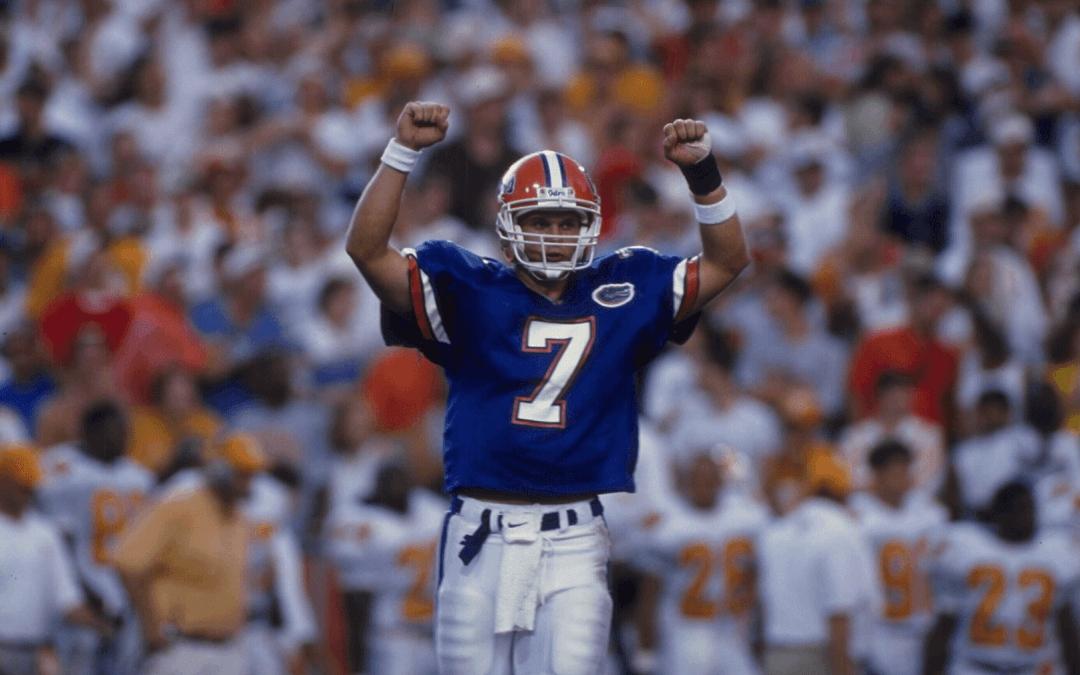

Still, Will Grier helped the team to a 6-0 start and there are legitimate football questions as to whether Harris can perform at the same level. Despite a strong performance against LSU, a better defense statistically than all but one faced by Grier, those questions persist and perhaps grow louder as the Georgia game draws closer. There are differences between the two quarterbacks to be sure, but the larger narrative about whether the “step down” between Grier and Harris is significant, as one writer stated last week, is an interesting and complicated one.

Statistically, the step down doesn’t appear at all significant.

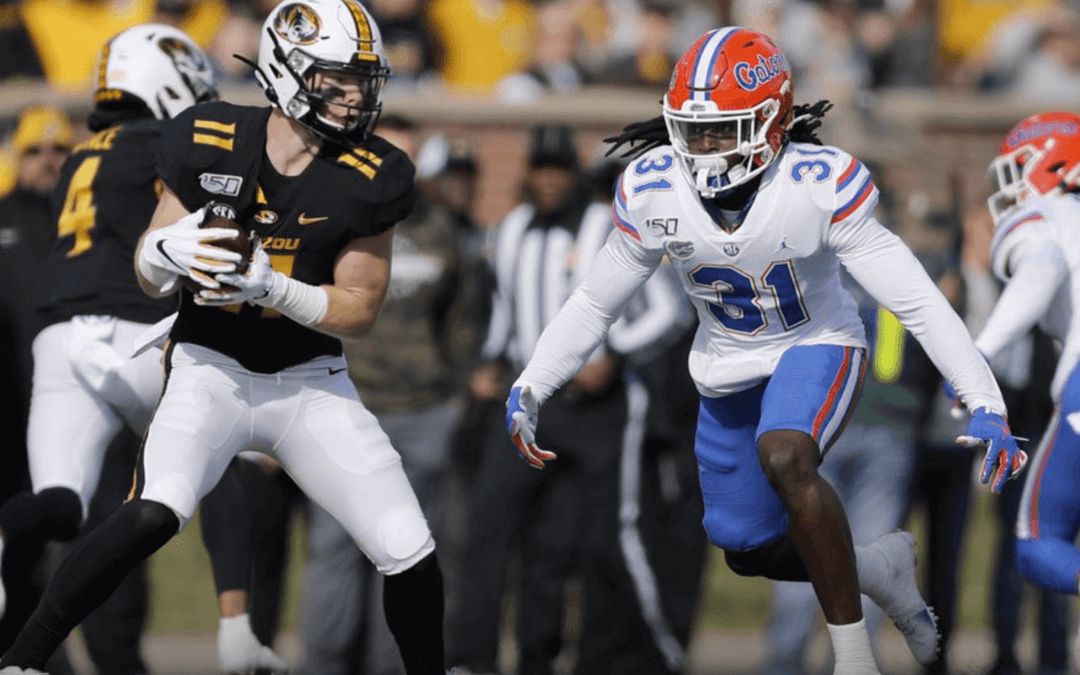

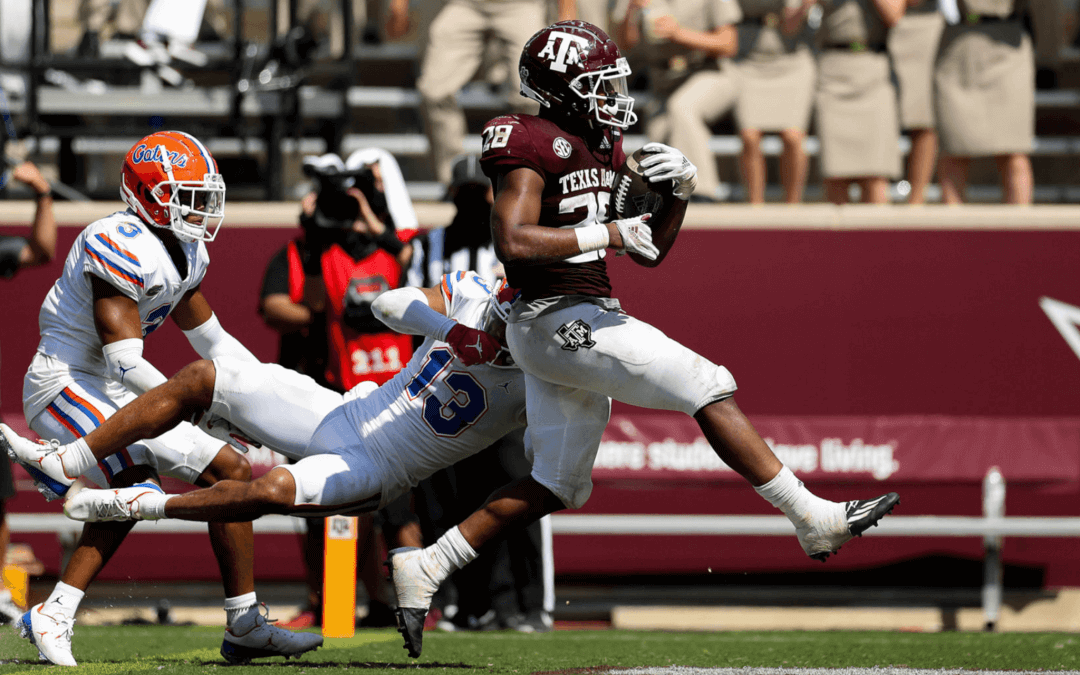

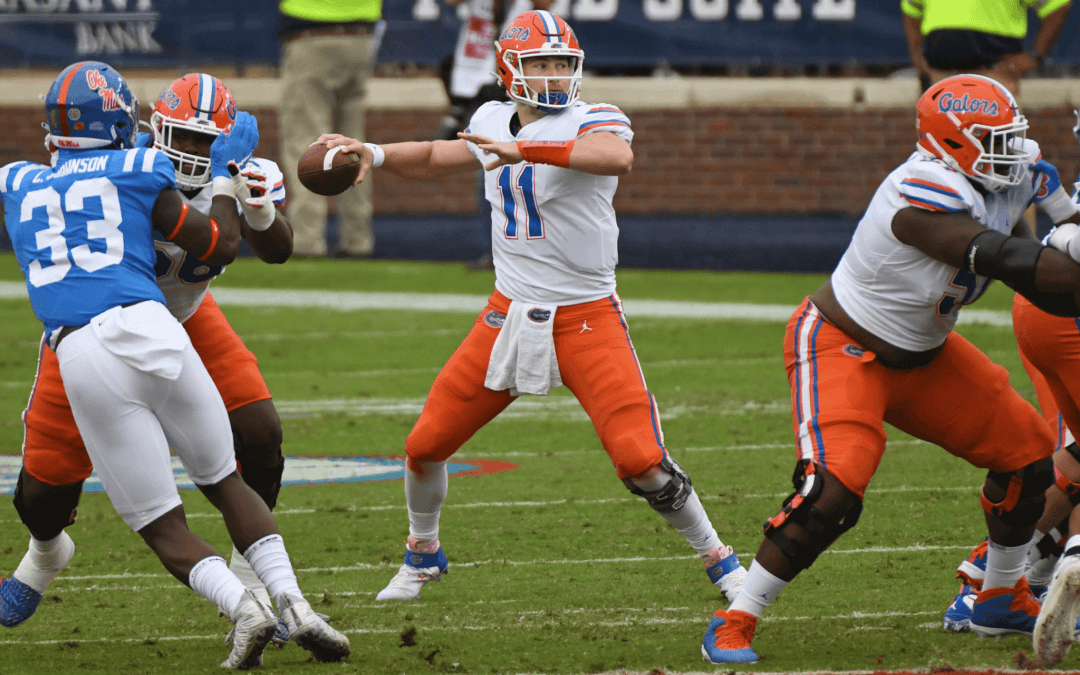

Against Missouri, the only defense Grier faced similarly situated to LSU in both total defense and S&P+ defense (explainer at link), Grier performed worse than Harris, producing less points, running offense less efficiently and getting routed in explosive plays. And this despite Florida running the ball reasonably well against Missouri to help the young quarterback out. Grier started the Missouri game with Jake McGee saving a pick and after two scoring drives, was ineffective. Grier was 5-8 for 56 yards on the two Florida touchdown drives in Missouri, but was a dismal 5-11 with only 54 yards in the second half that featured multiple three and outs. Certainly, Grier was brilliant in the rout of Ole Miss, but until dominating last week’s matchup with Texas A & M, an Ole Miss defense lauded as tenacious on paper had been timid in practice, surrendering 37 points each to Alabama and Memphis respectively.

Harris, as McElwain stated this week, likely saw some video from his second start of the season that frustrated him, and missed reads and underthrew balls, particularly on the Gators final two drives. But one wonders- or should wonder- if it is only because one game was a win and another loss that Grier received a pass from fans for a dismal performance against Missouri, while Harris’s flaws were roundly criticized after a good, by no means great, performance against LSU?

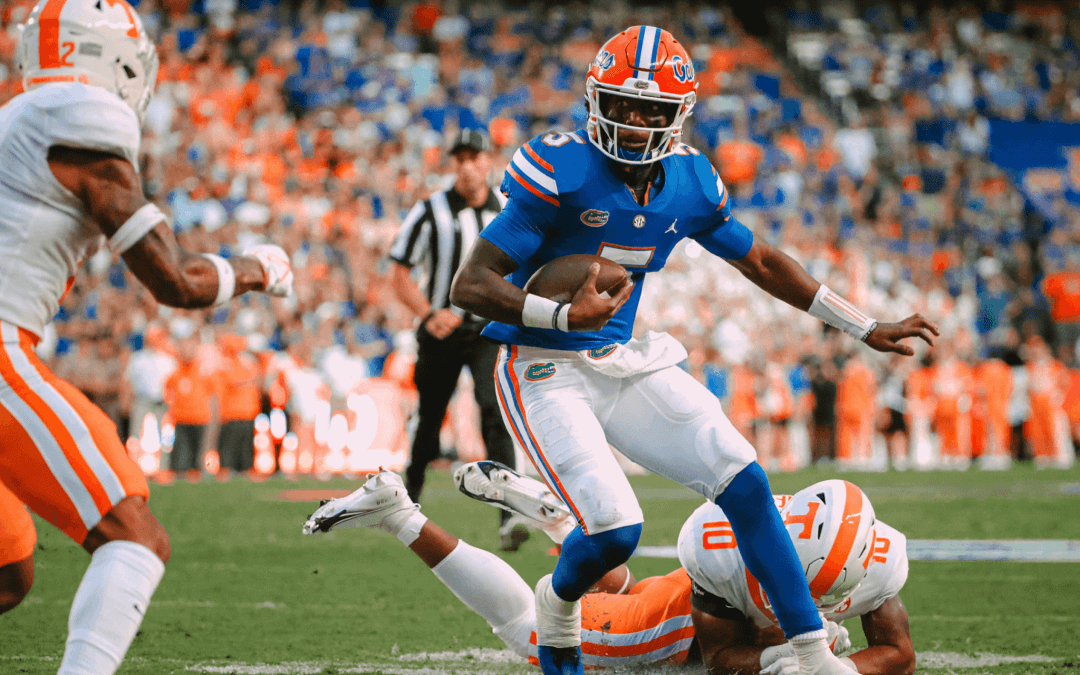

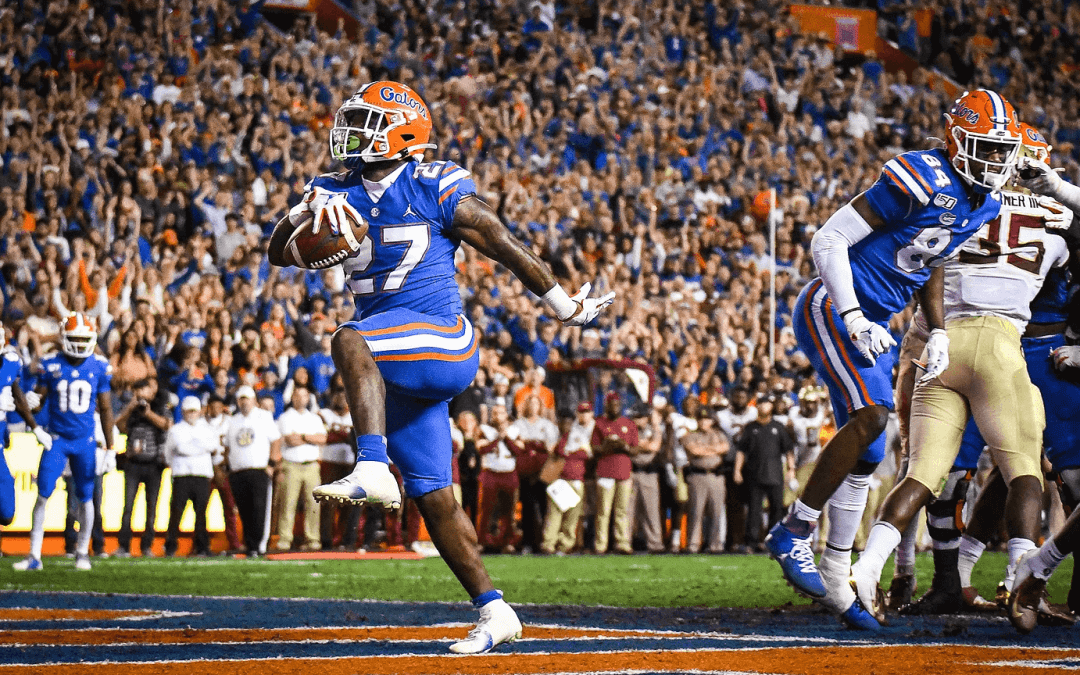

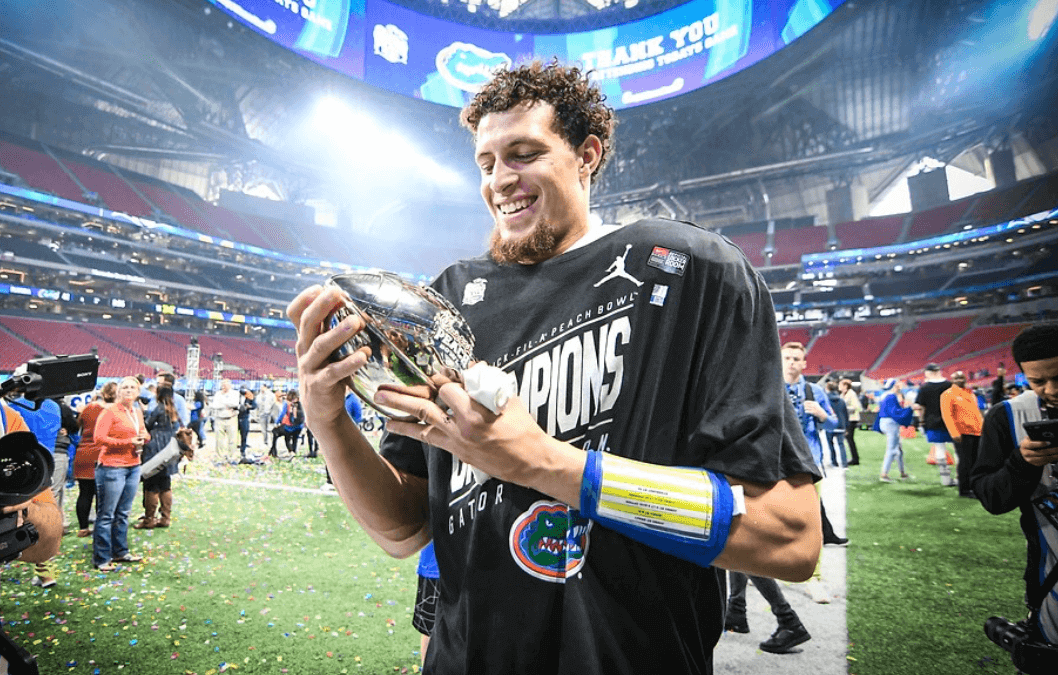

It’s a troubling dilemma. But given one is out for breaking the rules, Harris, starting his second Florida-Georgia game, is the only player who can add to the story Saturday. His coach, participating in his first, promises his quarterback will be ready. Will Grier, who showed terrible judgment in getting suspended but tremendous character in owning it, will watch from somewhere that isn’t the sideline, appeal ongoing, heart still broken.

***

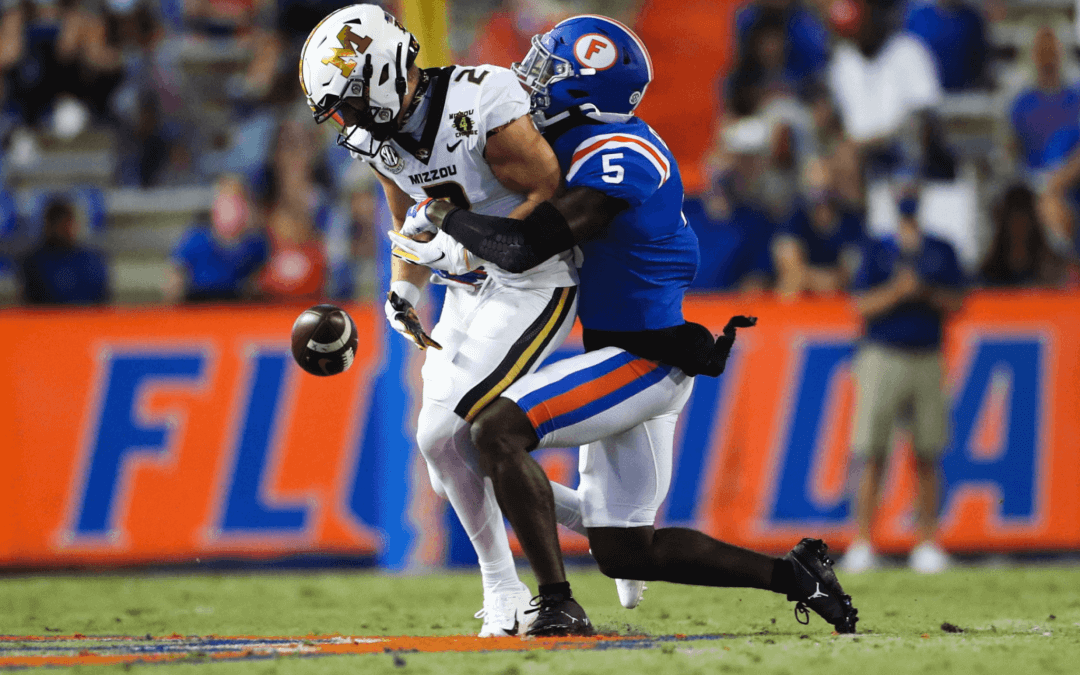

Heartbreak is part of Florida and Georgia. In 2002, as Georgia’s furious rally fell short, the legendary Georgia broadcaster Larry Munson’s (he of “Run, Lindsay, Run” fame) call of the Dawgs final, failed 4th down lingers in memory. “And they’ve gone and done it, those Gators. They’ve broken our hearts again. Ripped them right out of our chests.” Munson’s agony was worn in his voice and on the faces of the coeds leaving the stadium that night, mascara running, unbeaten season over. And it was felt in the pained, high voice call of Mick Hubert, nine years later when Jordan Reed fumbled inside the Georgia five yard line in the fourth quarter, the 107th failed Florida quest for an unbeaten season ending on the Everbank sod.

My sister was married that day in October 2012 and I didn’t make it to the game. In fact, I’ve been fortunate to only have to make one drive back from Jacksonville without a Gator victory. But I’ve thought about how awful that drive home was in 2007, when Florida didn’t rule the day, and the Saturday night bars at the beaches and Jacksonville Landing were painted red and black. That loss was to be Urban Meyer’s only defeat to Mark Richt and Georgia, and it propelled the Bulldogs to a Sugar Bowl season. That win, that night, made the heartbreak before redeemable.

I’m thinking of that game and theme as the Gators head into Saturday. In this magical season, is all the sadness of the past few years of Gator football somehow redeemed? Is Treon Harris redeemed, despite the fact that maybe he doesn’t need to be in the first place? As Gators and Bulldogs, maybe heartbreak is written into the contract.

After all, there is no happiness without something to forget. And the thinking here is neither side will soon forget this Cocktail Party.