Hey, guys. Those of you who are regulars on here know what I’m all about- Florida Gators sports, and the things I write- no matter the angle- are always aimed at a specific audience. But for this post, I’m targeting a whole new set of people, most of whom probably don’t know me. Because what I’m about to write is much more important than football, or basketball, or any sport Florida plays (which also means it’s much longer, but this topic deserves the nearly 4,000 words and two weeks I spent editing it. There are several pieces to this article, hence the section dividers, but trust me on this: it all ties together).

__________________________________________________________________________________

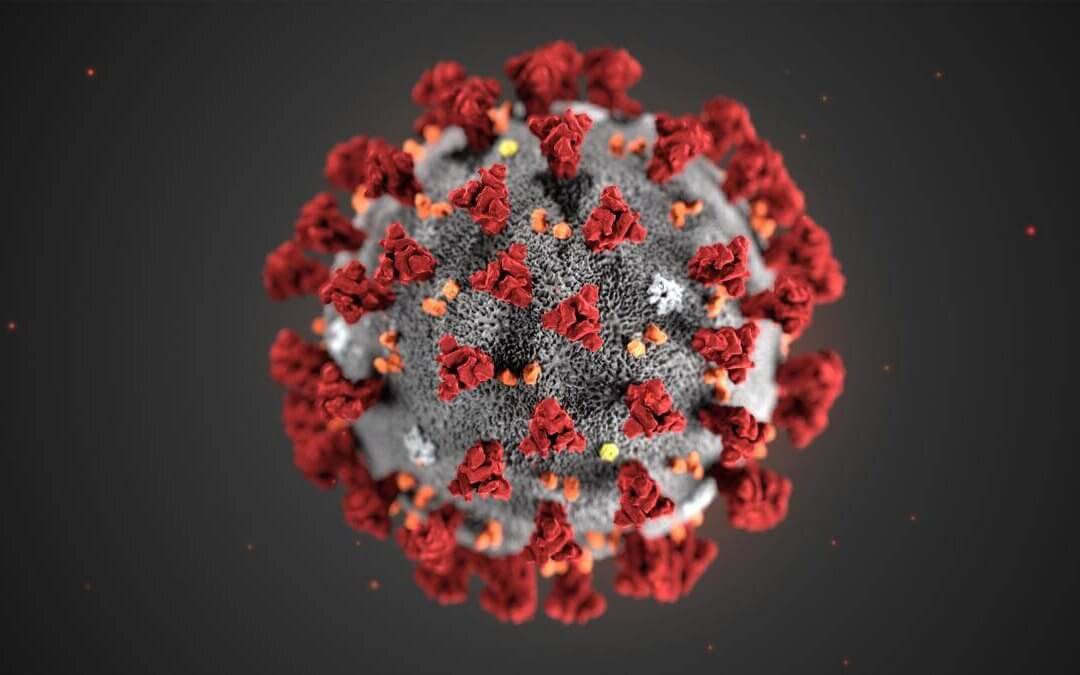

A couple of weeks ago, a 19 year old freshman at UPenn committed suicide. Her name was Madison Holleran, and she was my third fellow northern New Jersey student-athlete to commit suicide since I graduated high school in the spring in 2012, after Jerry Napoleon (who I knew personally and was friends with) and Paige Aiello (who I did not know personally, but knew of through mutual friends). Madison, like Paige and Jerry, suffered from depression, and sadly, saw no other way out of it than to end her life.

First, I want to extend my condolences to the family and friends of Madison Holleran. I’ve lost a good friend and a first cousin way too early, but not a child, sibling, teammate or best friend since early childhood, so I’m really not in a position to say something naive like, “I know how this feels” to those who can place Madison in one of those categories. All I can say is that I hope with time, the pain will slowly fade.

Second, I’d like to give a quick word of advice to anybody who may be feeling depressed/suicidal. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with coming out and admitting this to your loved ones; as a matter of fact, it’s a sign of strength.

Second, I’d like to give a quick word of advice to anybody who may be feeling depressed/suicidal. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with coming out and admitting this to your loved ones; as a matter of fact, it’s a sign of strength.

I read that line from Madison’s dad in an article about the funeral, and the more I thought about it, the more I realized he’s 100% right. Depression is an illness. It needs treatment, just like a broken bone or a high fever. In the cases of physical ailments, how would you think of one who was injured or sick, was all alone, and called for help? Would the person be looked at as weak? Or would that person be looked at with admiration, for being able to overcome his/her own sickness/injury to get to a phone and call help? It’s a bit different with depression, because it’s a mental illness and it doesn’t carry the same pressing physical discomfort of a broken bone or internal sickness that drives the person to want to call for help in the first place. But it’s still an illness, and even more so than with a physical injury, one suffering from it would be praised for coming out and asking for help. And since it’s never easy for somebody to say, it shows a lot of courage to admit that you’re depressed.

At some point, I read another article on Madison’s funeral, and I came across something else her dad was quoted as saying: he wanted to share the story of his daughter’s suicide in hopes that other people could learn from it and possibly use the knowledge of what happened to help others in similar situations. Well, there’s not a whole lot I’m able to do here, but this is one thing I can do.

________________________________________________________________________________

For those that don’t know me…. Hi, I’m Neil Shulman. I’m 19 years old, and a sophomore at Muhlenberg (PA). I was a four year starter (3rd singles first three years, 1st singles senior year) for James Caldwell High School’s tennis team (Caldwell, NJ), and was part of the most successful senior class in the history of the school. In fact, when I graduated, I’d accumulated the most wins in my school’s history (52) and received interest from dozens of schools across the country including two D1 schools, Richmond and Delaware (although more than half the letters/emails were form letters. Like, Hi, ____ we see you’ve had success in high school tennis as well as USTA, blah blah…).

Ultimately, I chose Muhlenberg (D3), because of the friendly atmosphere and the academics. At first, college was just like high school. Academically, the workload wasn’t too bad, and right off the bat, I broke into the starting lineup (though admittedly due in part to an injury) and got to the semifinals of the Southeastern Regional ITA tournament in Virginia. Not bad for a freshman, right?

Because of all the success I had in high school, both athletically and academically, and then early on in college, I expected the rest of college to be more of the same, but then both sides (academically and athletically) started to get harder… and harder… and harder, and the pressure started to build… and build… and build. I really had problems adjusting at first, and though I can honestly tell you everything’s fine now (thanks to my wonderful friends), I can not only understand the overwhelming pressure Madison was feeling, but I can, to an extent, verify it (and will soon explain it). And I’m at Muhlenberg- a very good school, but a far cry from Penn, so I know that as bad as I had it, she must have had it worse. We may not have known each other, and I may not have ever actually fallen into depression, but we did have one thing in common: we had a ton of success in high school, but the pressures of college got to us… and that’s where suicide among student-athletes can all start.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

The first step to suicide among student-athletes is usually mounting pressure, and you can help fight it by not adding to it in any way.

On its own, pressure isn’t what causes suicide, but that’s where it stems from. I can explain how (at least to a degree). Even though Muhlenberg’s not as rigorous as Penn in terms of schoolwork, and athletically, is D3 compared to Penn, which is D1, there’s a pretty stiff course load and the sports are taken just as seriously.

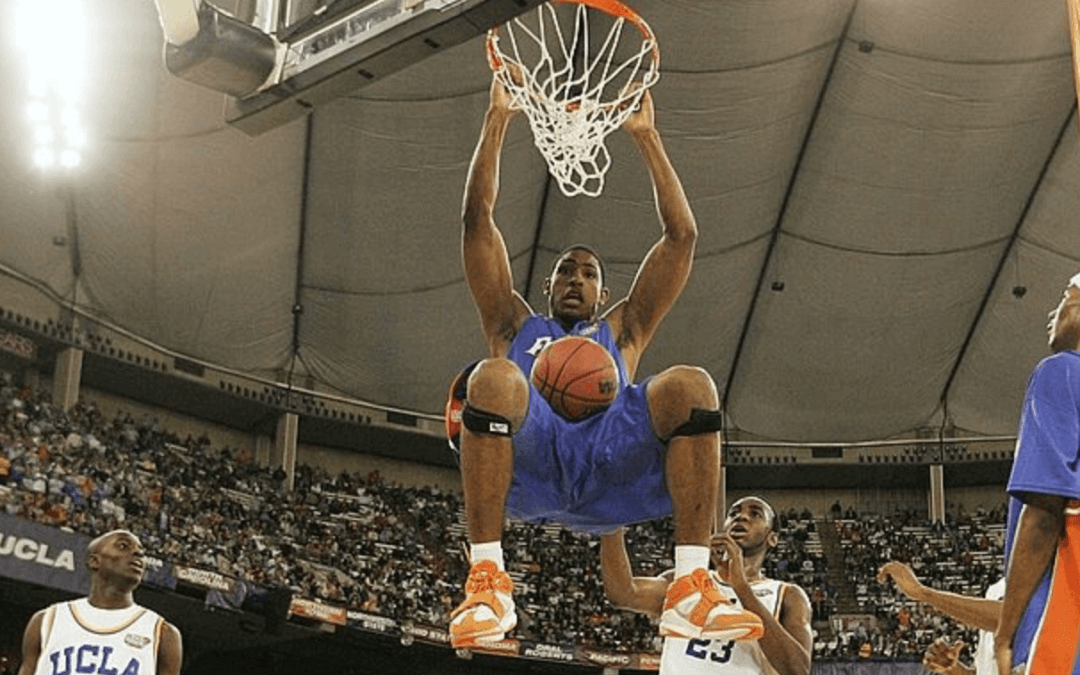

Perhaps just as important to the general difficulty of student-athlete life are the large blocks of time you’ve got to set aside for it, and maintain that focus throughout that period of time. Think: you’ve got to be 100% locked in mentally and pushing yourself to understand the material you were taught that day… in a class that’s (likely) harder than anything you’ve ever taken in high school. Then the next day, you’ve got to be right back at it, and the next day, and so on. Needless to say, this can get to be physically and mentally exhausting. This, of course, is in addition to being 100% focused physically in order to be better than your opponent… who more than likely dominated in high school just like you did. Your athletic opponents are going to be tougher on a regular basis than they were in high school, since not all your high school opponents are playing NCAA sports. Of course, the physical grind repeats itself the next day, and the next, etc. Naturally, this can get to be physically and mentally exhausting just as much as the academic side. This part, I can tell from personal experience.

Basically, it’s pretty easy to mess up in the slightest bit simply because your margin for error is smaller than it ever was before, and also because of the large quantity of chances to slip up… and this is without outside interference.

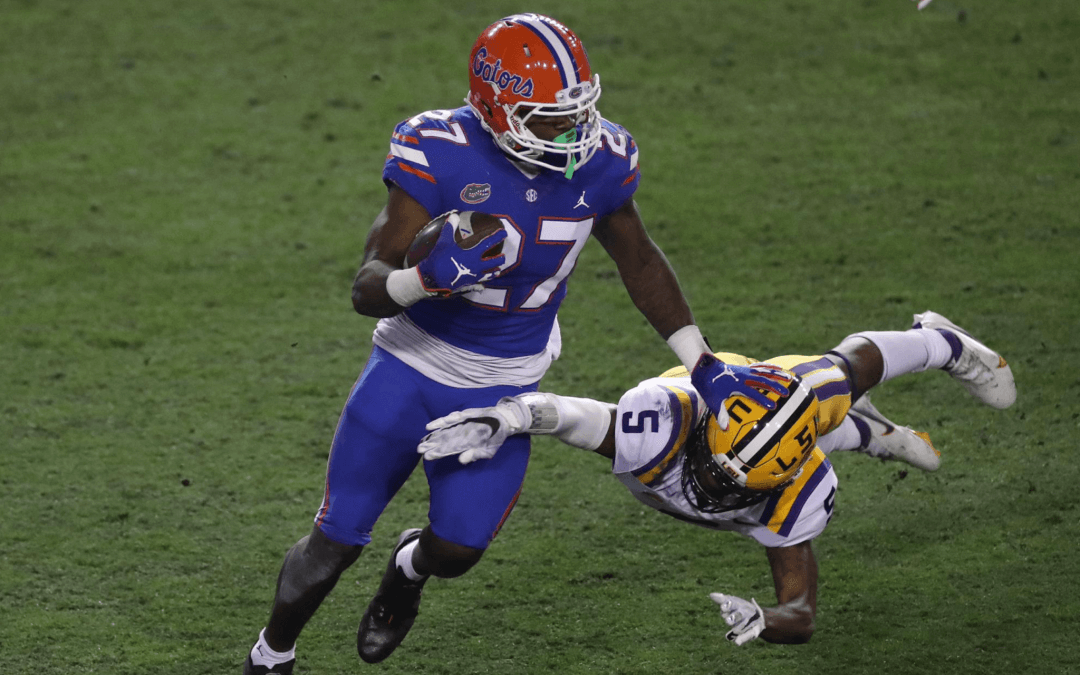

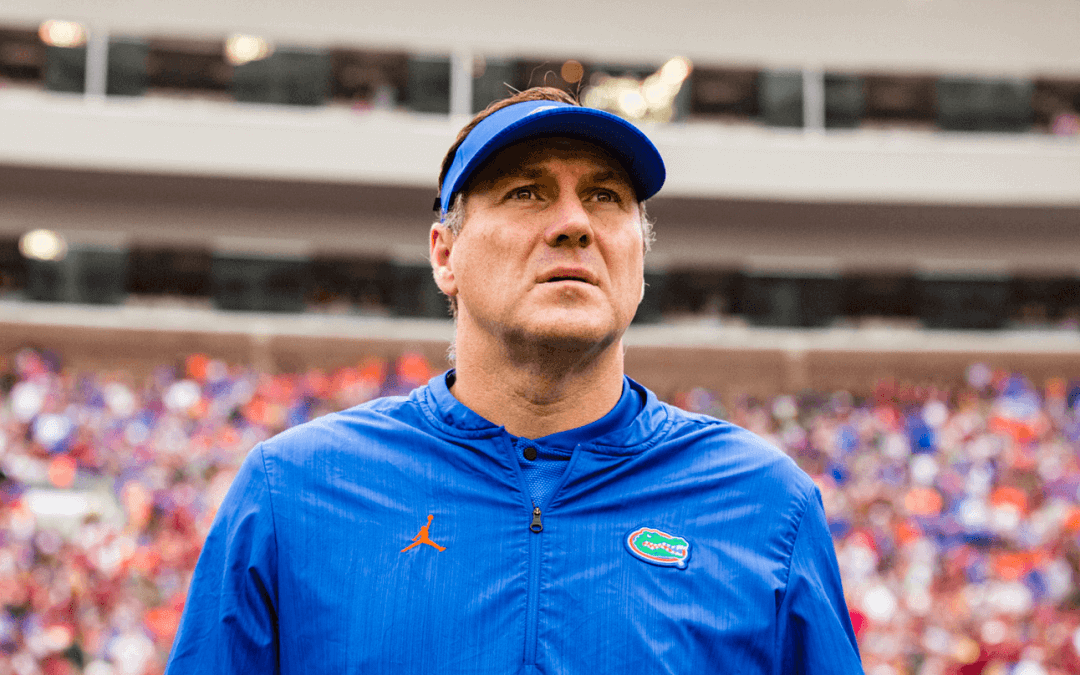

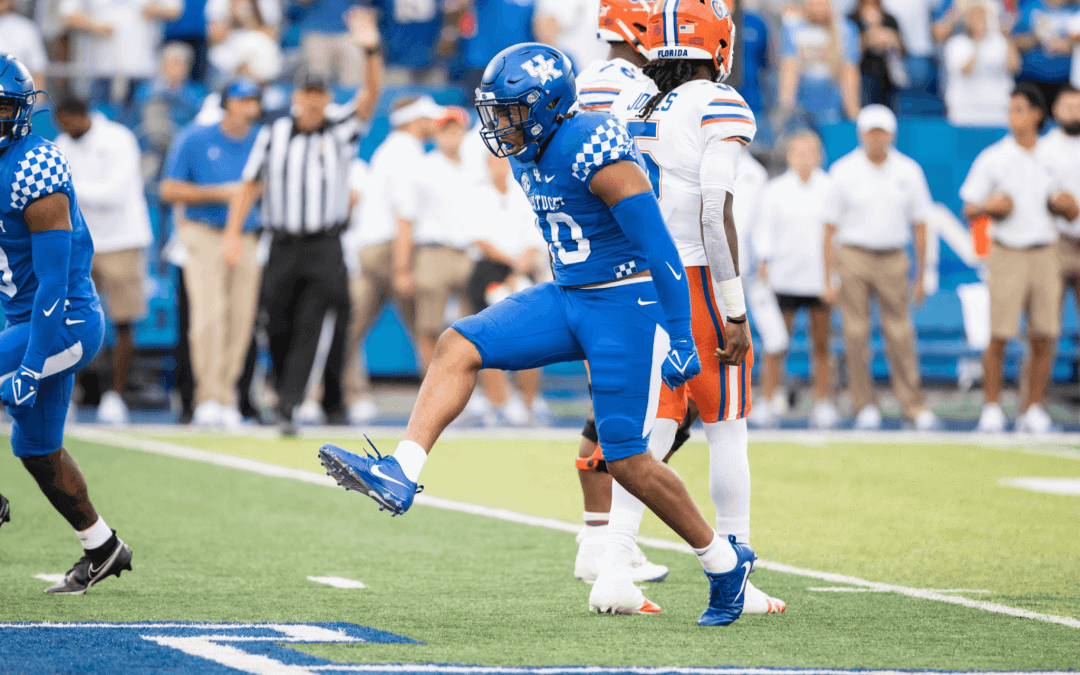

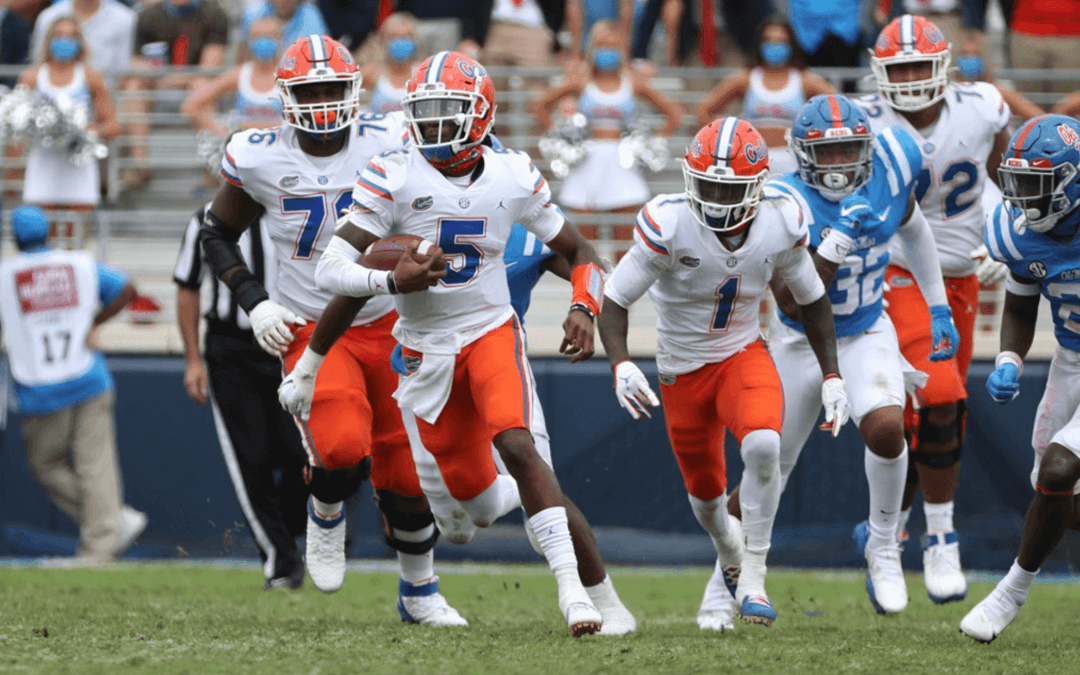

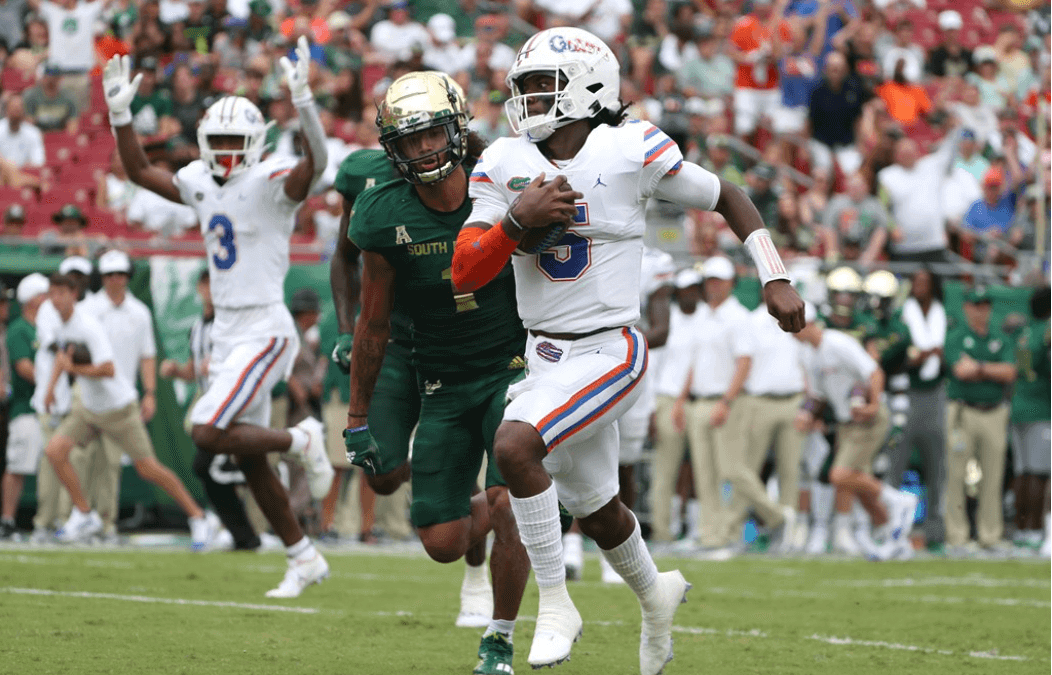

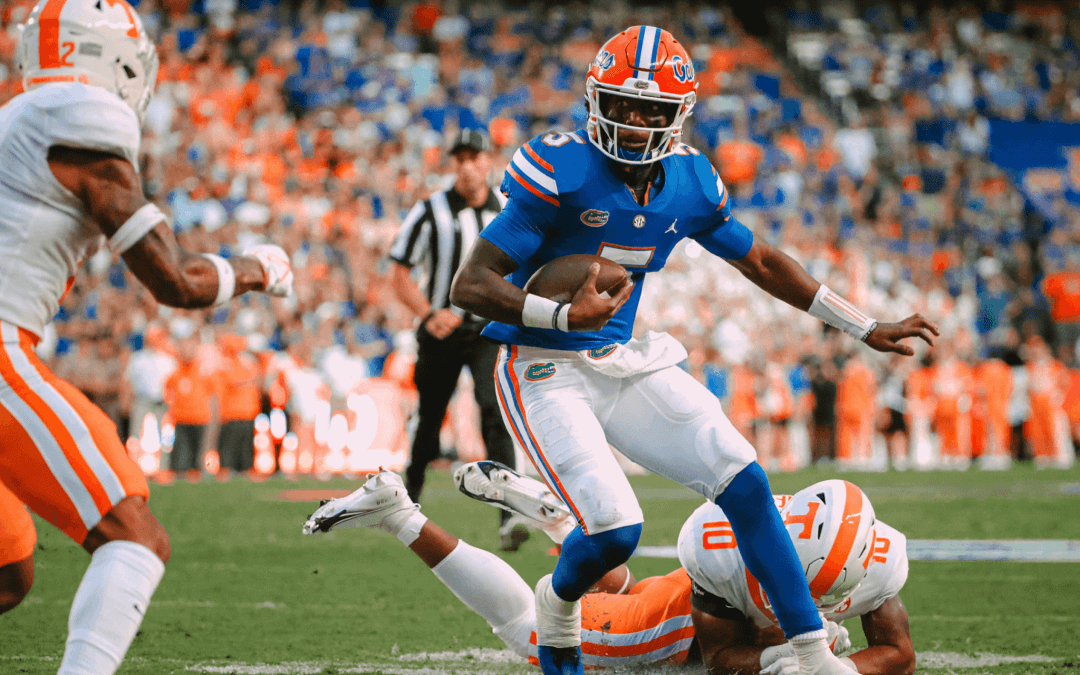

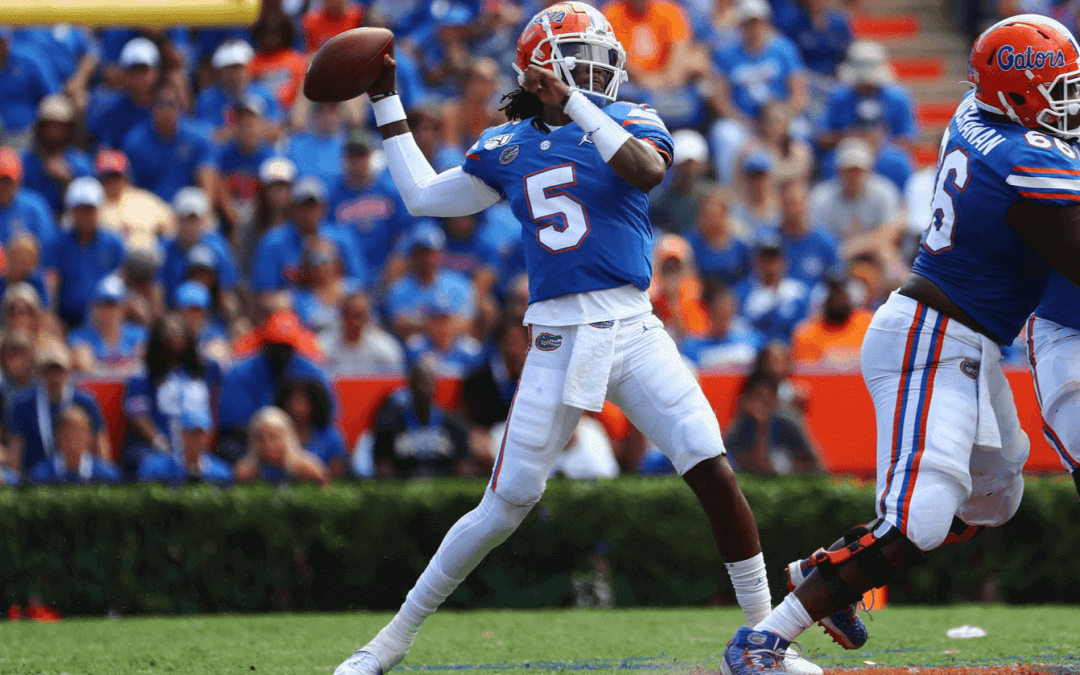

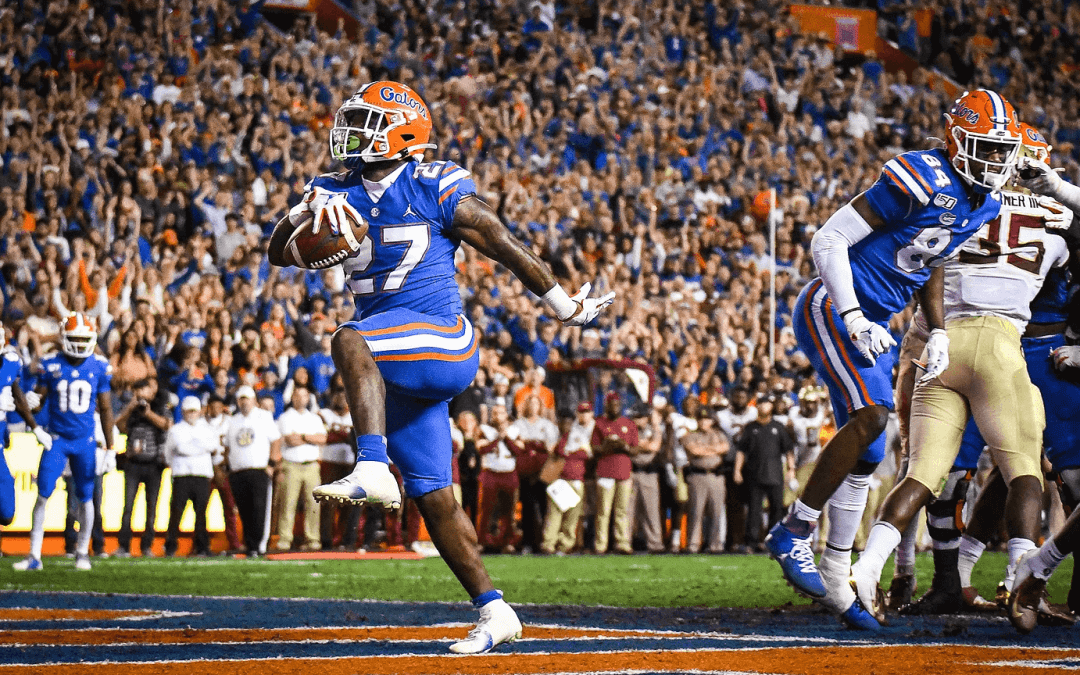

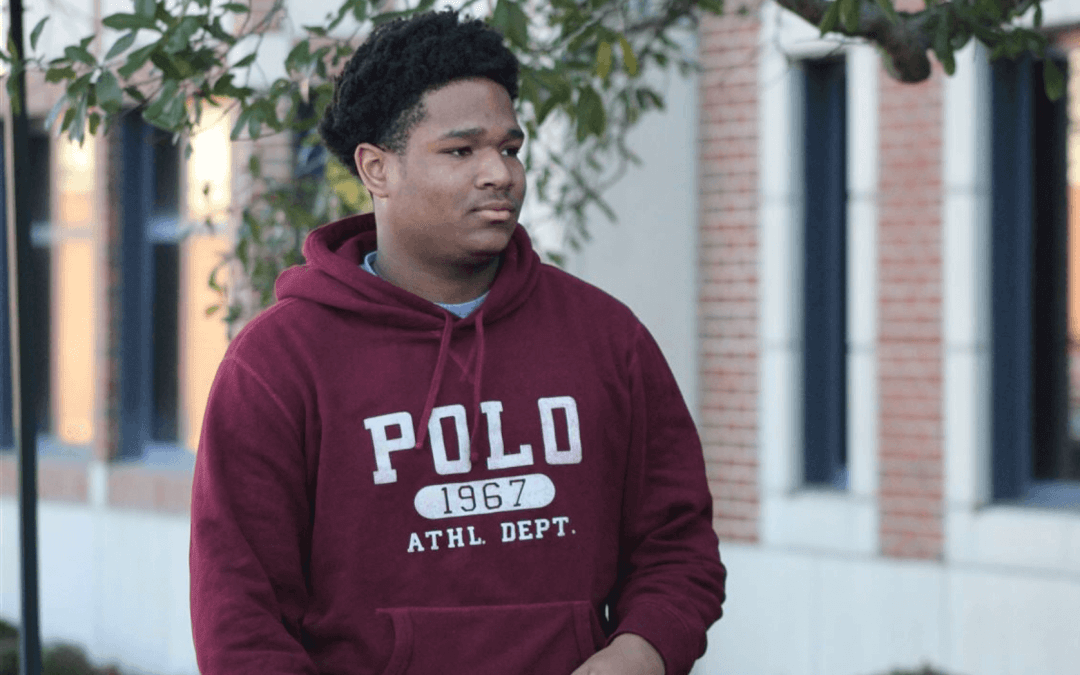

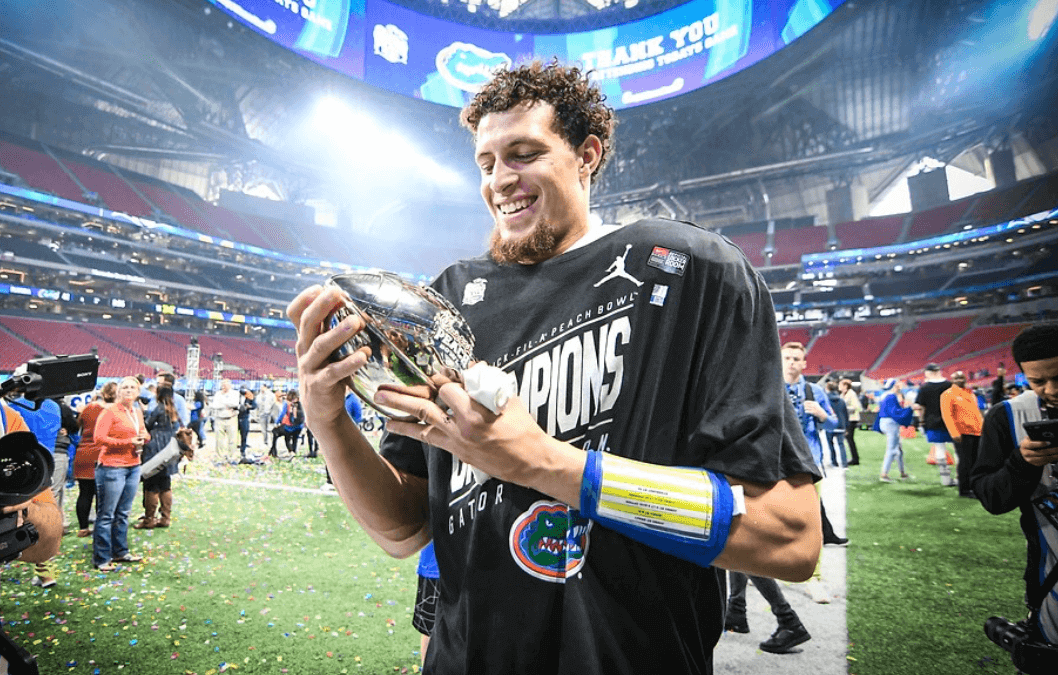

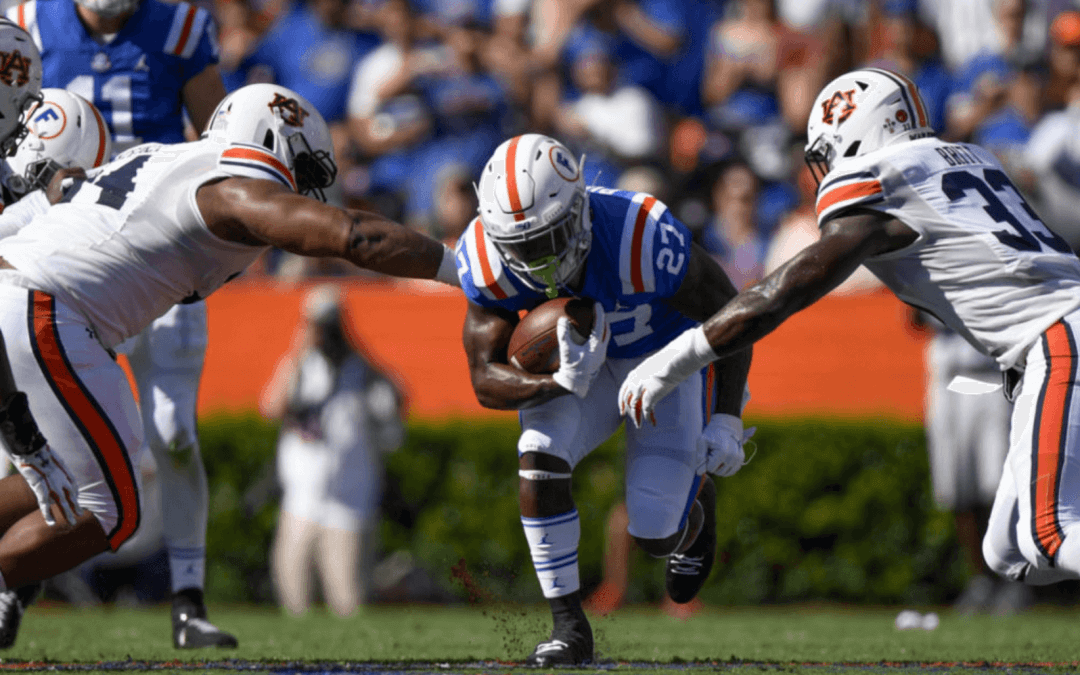

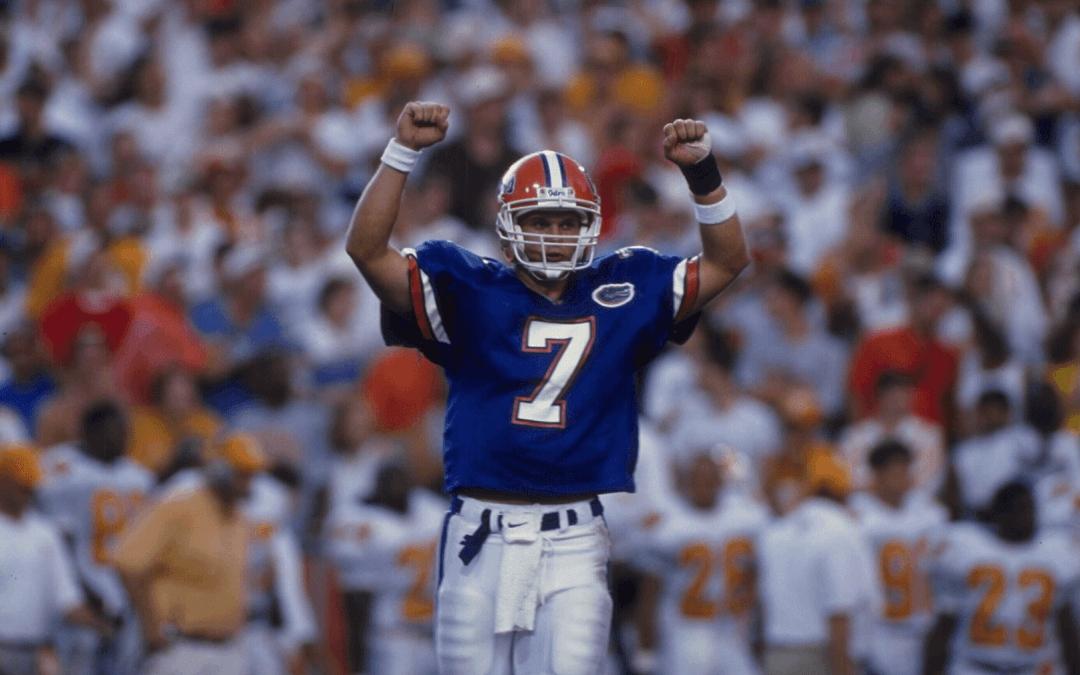

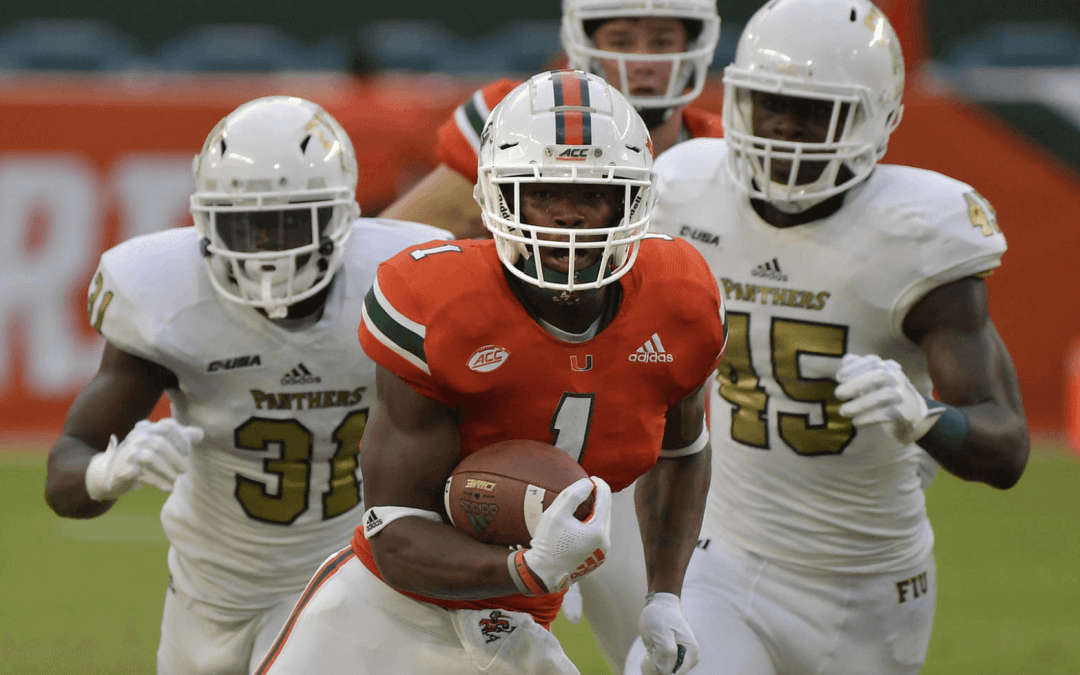

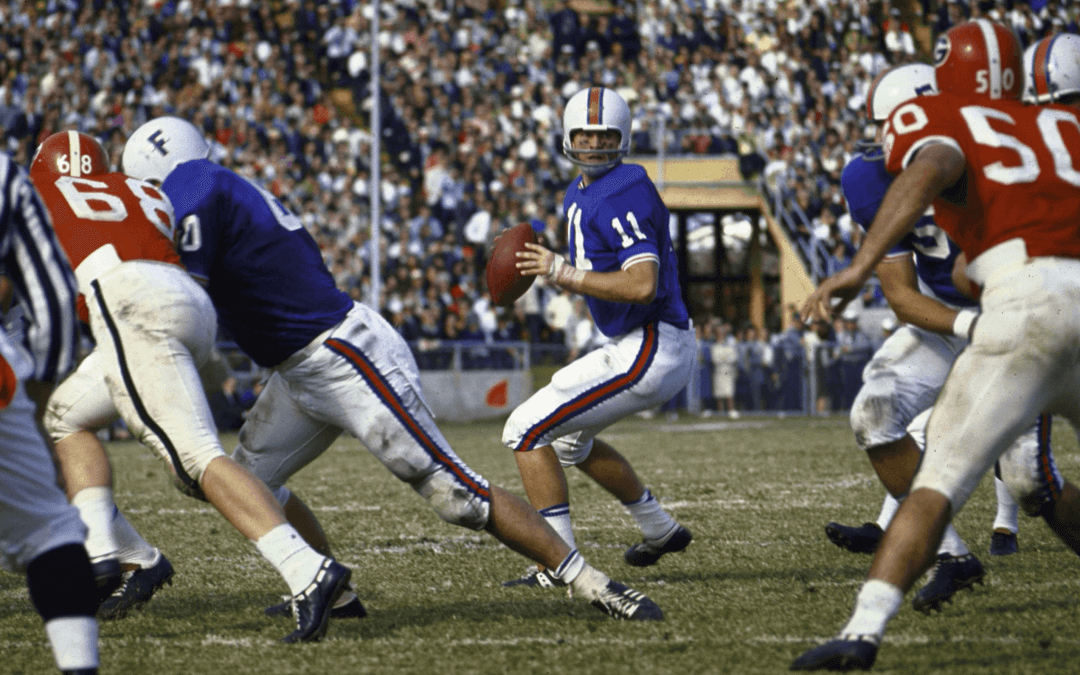

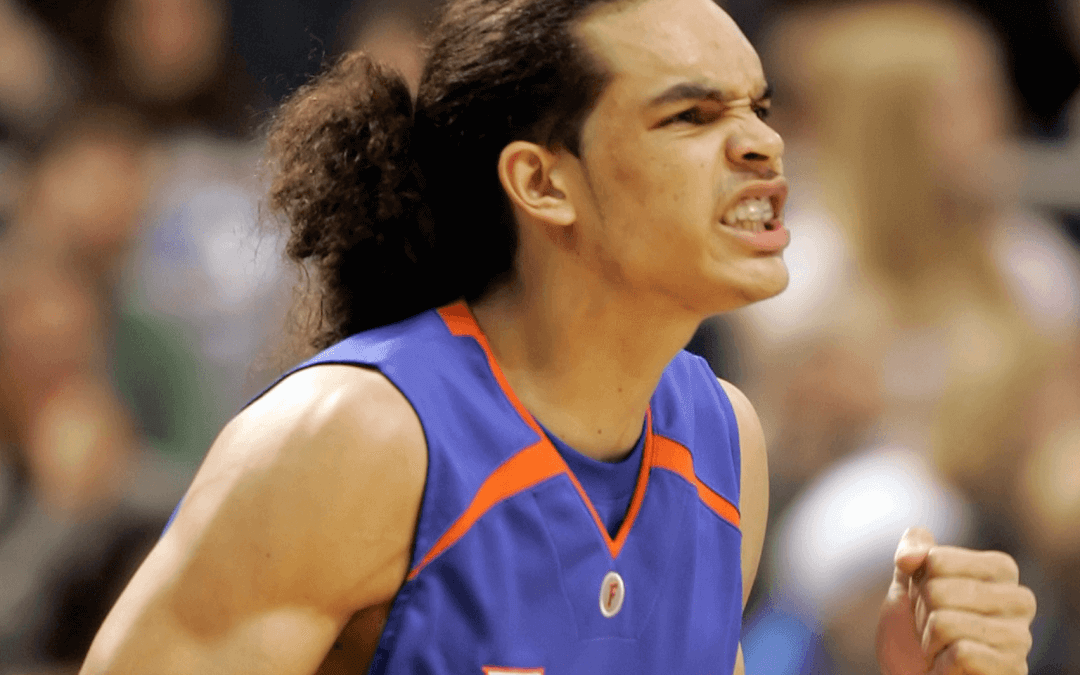

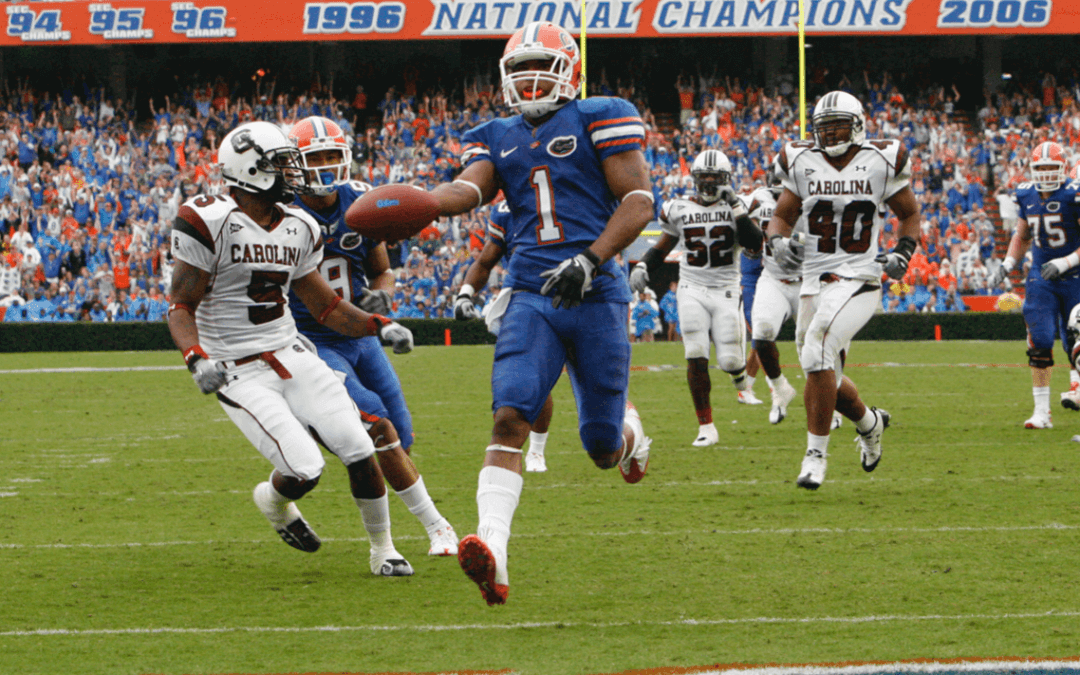

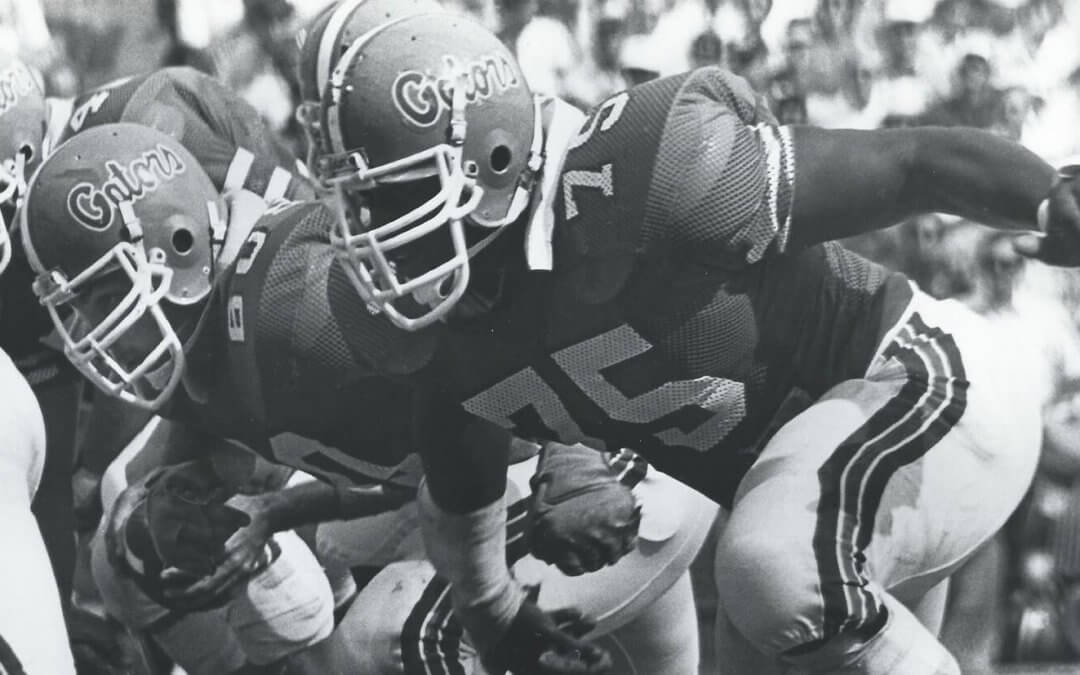

Take John Brantley for example, the QB from Ocala with the big arm. He commanded so much hype among Florida fans from the moment he decommitted from Texas and chose UF. Gator fans, remember this? 99 touchdowns in high school, which was a state record. Gatorade National High School Player of the Year. He’s gonna be another Tim Tebow (which was ridiculous because in reality his ceiling was Doug Johnson, and not just because he wore #12 and always overthrew his crossing patterns). Surely he’ll lead Florida to instant glory, right?

See, that’s a lot of pressure right away, before he even stepped onto the field. Predictably, Gator fans’ lofty goals for Brantley never came to fruition, thanks to injuries, a horrible offensive coordinator and bad luck. Regardless of who you want to blame for Brantley’s failure at Florida, the fact is that he fell victim to the immense pressure that comes with having to replace the iconic Tim Tebow, and thus, was a major disappointment. And when he failed on the field, the fans added to his misery by heaping abuse on him, both by littering the internet with stuff like this after he was injured and worse, by saying those same things to his face passing by him in the street and from the comfort of the stands, which, as you can imagine, only exacerbated his problems. As a fan, it’s your right to quietly curse out a player who displeases you, but doing it so he can hear it is where the problems start. I can personally relate to that, too; back when I was a real head case (not that long ago), I’d hear plenty of garbage from my opponents’ benches during my matches, and I didn’t appreciate it.

Luckily, neither Brantley nor myself let the additional stress lead them into serious depression. Brantley would just ignore the boos from his own fans and act like he was completely oblivious to it all, and (after I’d win) I’d taunt my opponents right back by doing stuff like bowing, or waving goodbye, or making yapping motions with my fingers followed by a throat slicing gesture (not proud of any of that, for the record). But whether or not it drove Brantley or myself into depression is irrelevant; that’s exactly the kind of stuff that could drive a student-athlete over the top, and sometimes does, like I believe it did to Jerry Napoleon (even though he’d never admit it, so I can’t say that like it’s fact). You just can’t be sure who’s already fighting inner demons to start with, and shouldn’t risk adding the backbreaking straw to the metaphorical camel’s back, especially not when bullying/abuse is an entirely different cause of suicide; the last thing you should do is try to combine those two different types of stress in one person, and I think that’s at least part of what happened to Jerry Napoleon (though to reiterate, I’ll never know for sure).

Now, I have no idea if Madison was ever really bothered or hurt by something anybody said, and it’s not my place to take a guess. Besides, again, this article is designed to prevent similar tragedies in the future. All I’m saying is that we can’t physically control a lot in terms of kids battling depression, but we can control this much.

Regardless of the source, though, pressure is where it all starts, and it can all snowball from there, very quickly.

_______________________________________________________________________________

The second step is the feeling of helplessness; the inability to fix the problem due to the lack of available time.

In life, when faced with a problem, your natural inclination is to fix it. Whether you get fired from your job, crash your car, or break a bone in your body, you then have to figure out the best way to deal with the problem. You get back up and look for another job, or call Triple-A, or 911. You don’t ignore it and make it worse. So when you’re suffering from immense pressure, you try to think of a way to overcome the pressure. The obvious solution? Do better in your sport and get better grades. How do you accomplish that? Put more time and effort into everything you do.

The problem is, as an NCAA student-athlete, there’s only so much time you have in a day to begin with. You need 8 hours of sleep to really function, so that leaves just 16 hours to do things. Subtract about three more hours a day for classes, which puts you at 13. Then take away two more for practice, leaving 11. Take away another hour to eat your meals that day (and that’s if you eat quickly), to make 10. That about sums up all the tangible things with time limits that you don’t control that you have to do every day.

So, before you’ve even touched your homework, reviewed your notes, or walked into the gym to keep yourself in top shape, you’ve got roughly ten hours of free time every day. I know, that looks like a lot of time, but when you have to manage it so carefully, it really isn’t. At this point, it’s totally up to you to divide up the ten hours to ensure top performance in your sport and your classes. Generally speaking, I spend about six hours a day re reading my notes, doing homework problems, doing required reading assignments and seeing my professors- because that’s what I feel I have to do in order to get good grades. Then I spend another hour either going to the gym, running or working out in my own room. That leaves me with a grand total of three hours to kick back and relax a day… and this is as much as I’ll ever get. Play with the numbers a little if you like, but that’s the general daily routine for a student athlete. You can’t even be guaranteed to get three hours of time to yourself.

How about, for example, when I played in the ITAs in Fredericksburg, VA? That’s a five hour drive with no traffic, and it killed an entire weekend of work. Doing homework on a bus, even one as nice as our team got with tables, wifi and TVs, is impossible for more than a fraction of the time, and even when you are actually doing work, the temptation to hang with your teammates, or watch TV, gets to you and you rush through it, diminishing the quality. That’s as far as we’ll have to travel (and it’s only once a year), but we frequently make 1-3 hour road trips that take away entire days of work. Then there’s the aspect of the actual match, that adds on to the driving time- matches/games/meets generally take longer than practices. Even for a home game, you’ve got to allow more time than usual. Better yet, what about when you’ve got a big test coming up? You spend more time than usual reviewing your notes in the days leading up to it- you have to- so that eats into your three hours of free time as well.

Tests and matches/meets don’t happen every day, but they’re certainly not infrequent. They happen often enough that you have to have a routine for them- a more intense one than normal. So when you lose some of your free time on some days for matches or tests, you can’t get them back, and if you try, you risk a drop off in either your studies or your sports. Never mind that school comes first; in a student-athlete’s mind, they are obligated to perform both. Quitting your team is a possibility, but from what I’ve seen, that is rarely, if ever the route student-athletes tend to go when they’re getting decent playing time. They just can’t bring themselves to do it, and being a pretty intense competitor myself, I can completely understand why they wouldn’t want to give up a good spot on their team.

But over time, having three hours of free time at best and sometimes none can really get to you. Worse yet, if you’re feeling the pressure of having to perform, and you decide that you need to allot more time to your two main responsibilities… well, where are those extra hours going to come from? You do have a choice, but both possibilities come with their caveats: you can take away some of your sleep and relaxation time to spend more time and effort on your academics and athletics, but risk burning yourself right out until you’re a mental and physical wreck, or you can just try that much harder with the same hours and hope for the best, but without an immediate and drastic improvement, it’s quite possible that you’ll get discouraged, which is somewhat less than ideal.

__________________________________________________________________________________

At this point, some people don’t see any other solution than to commit suicide.

Of course there are different, better ways to handle a situation than that; for each potentially suicidal person, there may be a different course of action, and since I don’t know everybody in the world and what would work for each individual, I’m not going to list any suggestions. Trust me though, there are plenty of other roads to take, each one of them better than committing suicide.

The most frustrating part about depression is that even the best psychiatrist or therapist could give exactly the advice they were taught to give, and it might not help. Think about it from a student-athlete’s point of view. How is some random person telling me to try this exercise or that exercise going to improve my 800 meter time, or boost my B+ to an A? It won’t give me Usain Bolt’s legs, or Albert Einstein’s intelligence, etc, and it won’t magically add four hours to my day. Whether thoughts like those are full of fallacies or not is irrelevant; (and I’m not saying it is or it is not) it’s what goes through too many peoples’ minds, including my own, and in some cases, it’s simply not possible to change somebody’s mind about this. Of course, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try, because, in perhaps the biggest understatement ever written, it’s better to give it a shot and fail than not try anything at all.

Anyway, once a person has determined that he/she tried everything and cannot correct the situation, they may tend to lose confidence in themselves, and that’s pretty much the end of the explanation of how it can happen. I don’t know when Madison, Jerry or Paige lost all confidence in themselves, but at some point, I believe that they must have and seen no other way out.

Again, I’m no pro at this, so I’m not in any position to guess what might have done it, but there had to be a snapping moment that finalized the decision, and, well, you know the rest.

_______________________________________________________________________________

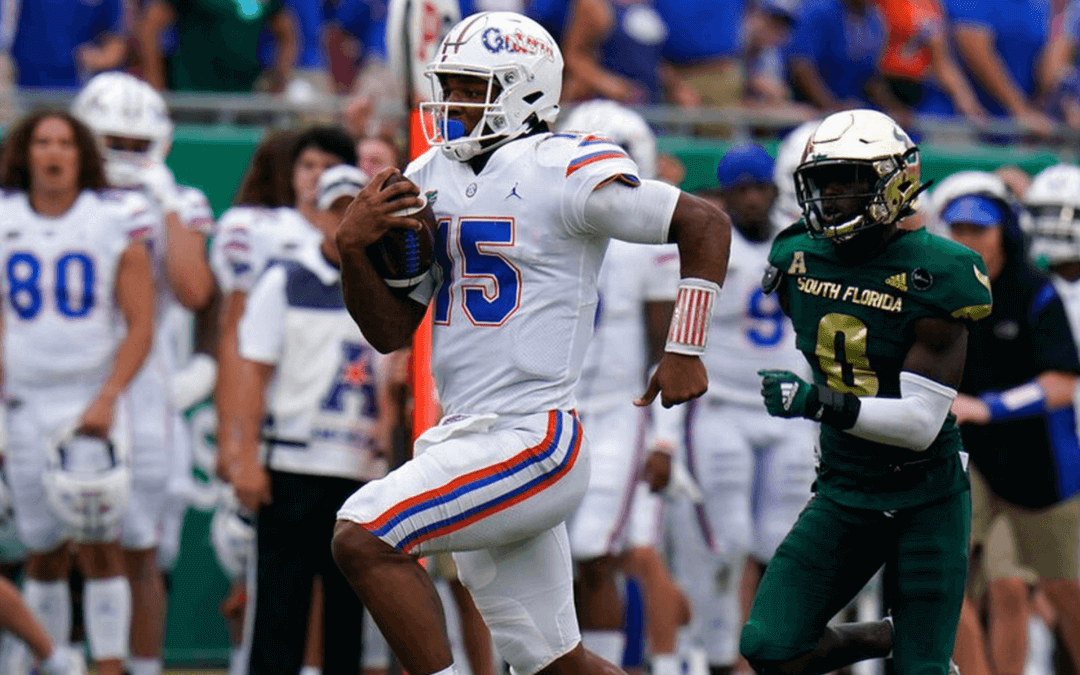

Try to put yourself in my shoes, or Madison’s, or Jameis Winston’s for that matter. We all seem/seemed extremely happy, loving life, etc. I’m doing pretty well now, Jameis seems to be OK as well… and Madison appeared to be, too. But know that anybody who fits that student-athlete profile will always be under a lot of scrutiny regardless of whether or not they seem fine, or even whether or not they really are. Keep that in mind, in however you deal with them, and that’s all I can ask; there’s nothing more I can really suggest in terms of physically helping stop it as an outsider.

(Update 2/13/14: I talked to three former NCAA student athletes who suffered from some level of depression in the week since I first published this. All three asked to remain anonymous, which is an unfortunate bit of proof that coming out and admitting to being depressed is extremely hard to do, but of course I’ll respect their wishes (one did allow me to say that she played soccer for Minnesota at some point over the last five years). But as strong as their personal stories could potentially strengthen this article, that wasn’t even the purpose of talking to them.

After establishing the fact that they were depressed to some degree, I asked these three former student athletes one simple questions. How would your friends describe you? All three told me that they were described as being among the happiest people their friends had ever met. The point is, Madison was not exactly an anomaly. Sometimes, the happiest seeming people are the ones suffering the worst, and unfortunately, sometimes they’re the ones who take action like this.)

There’s one more thing I want to bring up before I close.

After reading how Madison’s father said he hopes this story would help others learn I realized that wasn’t the first time I heard that. Spreading awareness of suicide seems to be a common goal among families and friends of suicide victims, and this case is no different: Madison’s friend and old soccer teammate, Heather Ford, is doing something fantastic. She’s going to run a half marathon in NYC on March 23rd, and is dedicating her run to Madison by doing a fundraiser in her memory, and the money she raises will go to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Like Madison, I don’t know Heather Ford personally (other than sending her this article ahead of time to make sure it was OK with her), but since student-athlete suicide is a personal issue to me, I thought about donating to her page help her out. Then I realized that I can do better than that. But I need your help, Gator Nation. It starts with you, and it’s up to y’all to spread this to everybody, not just Gator fans. If you can spread this article to people who don’t read me normally, like friends, family, Facebook, Twitter, etc. and get this post, say 20,000 hits, or more, and everybody who reads donates even one dollar- well, the math speaks for itself. So please, folks. I know Gator Nation is a proud and wide fan base, and I know you’re good people. Help fight depression and suicide by donating what you can to Heather’s page.

The purpose of Heather’s fundraiser, like this article, is deeper than just raising money, though. Awareness of suicide is what’s ultimately the most important- how can we as a society possibly help stop it if we’re not all cognizant of it? Sure, you can say “suicide is bad”, and you’re “aware of it”, but how many of you who say that in principle actually give/gave your undivided attention to guest speakers (who, unlike me, are trained pros) who come into your school and talk about this? Young people need to take this seriously, because for all they know, it could be their best friend who’s possibly depressed and/or suicidal. I’m well aware of the general attitude of a lot of people my age, and younger: “Well, that can’t happen to ME. It won’t be MY friend who does it, so it’s not of personal importance.” Guess what? Madison’s friends sure didn’t think it would be their best friend to fall victim to depression, and eventually commit suicide- her friends have since talked about what a happy person she was- yet that’s precisely what happened. Just like I said with the student-athletes I talked to, the happiest looking people can just as easily be the ones to commit suicide as the least happy looking. So you never know who’s on the brink of snapping, which is why you should always be careful.

Bottom line: nobody knows how serious suicide is until they either experience something like this themselves, or read enough real life examples about it. That’s where I come in. I was so deeply saddened upon hearing Madison’s story that I decided to help her friends and family out in the only way I could- by spreading awareness of suicide among student-athletes by writing this, just like her father said he hoped people would do, because I can personally relate to some of the steps than Madison faced during her struggle, and others that she didn’t necessarily face, but are nonetheless potential factors in depression in general.

As I’ve said, I’m not a professional, or even close to one, but I would recommend you speak with people who are and listen to them. And it goes without saying: be on the lookout for signs of depression, and if you ever see something, say something immediately to an adult who you trust will handle it and put the depressed/suicidal person in the right hands. I do realize that it’s almost never that easy. Despite hiding it well, Madison actually told her parents of her depression, and they did the right thing: they put her in therapy. Her friends never had any reason to be suspicious of anything because Madison never exhibited any signs. Yet, nobody was inside her head at the end, the same way nobody can be in the head of the next tragic suicide victim. So I’ll say it one more time: be careful and sensitive in how you interact with student-athletes. You never know what they’re going through, and you never know if what you say or do could trigger something awful. That’s the lasting impression I want to leave.

I’m going to end by saying that I sincerely appreciate y’all taking the time to read this, and hope you’ve learned something. If you want to know more, talk to a professional, because, just to be clear, I am certainly not one. In any case, thanks for caring enough to put the time in to learn the little bit of advice I have to offer, and I hope you keep the message in your head forever.